“Our politicians are using people as a weapon of war”: Divisions in Bosnia are festering

Thirty years after the war, populism and the political system block reconciliation

Special Envoy to BosniaIt was only a few hours ago that Muslim families had buried their dead in the annual ceremony, when music broke the silence of the Srebrenica night: "This people will live [...] because God is also Serbian; the heavens are ours." A song by Serbian ultranationalist Baja Mali Knindža played through loudspeakers on the church side. His lyrics often glorify Serbian identity and openly disparage other peoples, especially Croats and Muslim Bosniaks. "You're leaving, Turks of Banja Luka. Don't touch our Serbian Republic. Pack up your things and flee to Turkey. Alija [Izetbegovic, former president of Bosnia], you are no longer the leader. You have defeated the Orthodox people," the song continues.

This episode is not anecdotal. Symbolic violence is part of the Bosnian landscape. Thirty years after the end of the war, this country remains stuck in the past. And despite attempts to move on, the grieving process has become entrenched due to dysfunctional institutional structures.

The Dayton Accords put an end to five years of bitter conflict between neighbors. Signed in this American city and promoted by the United States, they were supposed to provide a definitive solution for Bosnians. But what was supposed to be a way to overcome the war turned into a dead end. Dayton, which established the new legal and constitutional architecture, instead of uniting the country, institutionalized its ethnic divisions.

The war had pitted the country's three largest communities against each other (Orthodox Bosnian Serbs, Catholic Croats, and Muslim Bosniaks), who actually share far more than they do: a common language, a common cuisine, a common history. In the heart of Sarajevo, a mosque, a Catholic church, and an Orthodox church coexist within a mere 30 meters of each other. Before the war, the city was a model of multiculturalism, which is why Bosnia was called Little Yugoslavia. Thirty percent of marriages were mixed, and the presence of communism for so many years meant the rate of secularization was very high.

Yugoslavian nostalgia

A souvenir seller smokes a cigarette in front of her stall at the Sarajevo market. Tito's face appears on magnets, mugs, even T-shirts. "Yugo Boss," one reads, referring to the German fashion brand. It's "Yugonostalgia." "Tito good. Now, no""I'm not a man," the woman says in rudimentary English. This sentiment, described by so many writers born in communist Yugoslavia who, with the country's dismemberment, felt orphaned, is shared by a generation. And, in fact, it's the great consensus of Bosnia's three nationalities: they lived better under Yugoslavia and now think the politicians are more corrupt and inept. That's why they dislike politics.

These days, around the anniversary of the Srebrenica genocide, many pedestrians in Sarajevo wear a white flower with a green center on their chests, symbolizing solidarity with the victims and their families. It's everywhere. But when we cross the line separating the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina from the Republika Srpska, the landscape changes and fills with Serbian flags.

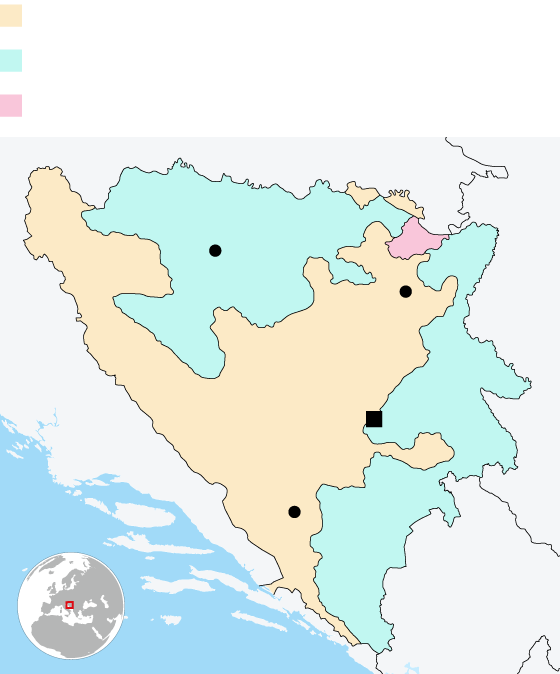

After the war, the country was divided along the lines of the territory dominated by the two opposing armies: the Republika Srpska, the territory controlled by Bosnian Serbs, and the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, where the majority of the population is Muslim and where the majority of Croats also live. To balance forces, the Brcko district, a neutral enclave, was created. But the division is not only administrative. It is also identity-based. The system requires that every citizen be assigned to an "ethnic group" at birth. Based on this choice, which appears in the form of a flag on their ID card, they can vote for one candidate or another in the presidential elections. For this method to be equitable, the presidency must rotate: every six months, the president changes. In this way, political continuity is impossible. And empathy between communities, diminished by the wounds of the conflict, is complicated.

Populist Speeches

The implementation of the peace agreement is overseen by the High Representative, a position established by the United Nations and currently held by German Christian Schmidt. This position arouses a certain resentment among the population, who feel that their elected representatives are subject to the arbitrary power of a figure not democratically elected. This further fuels populist and identity-based rhetoric.

The most striking example of this trend is Bosnian Serb leader Milorad Dodik. This leader has won elections with such harsh proclamations as denying the Srebrenica genocide and glorifying war criminals in his campaign. "I don't take them as their own," Dea says of this politician. "They are bad people because they use their own people as a weapon to wage war, not to make peace." On the outskirts of the city, however, posters present him as a hero on a television game show.

Sarajevo residents walk without pausing before the invitations to remembrance that inhabit a city so steeped in history. They are tourists fixated on the memory of the war. A group stops before the so-called Sarajevo roses. They are small holes in the ground formed by the impact of shrapnel during the war, when the city suffered the worst siege of a European city in contemporary history. Citizens filled them with red resin—evoking the color of blood—to remember the traces of the martyrdom suffered by the capital.

Despite the omnipresence of the memory of the war, young people are trying to make a place for themselves in this country anchored in the past. Sarajevo's terraces are filled with young people who want to be on vacation: to enjoy a good conversation, a stroll as the sun begins to set. "The tension that once existed no longer exists. People are moving forward. I have many Serbian friends. But it's true that politicians don't help," laments Mohammed. Dea and Matea share the same opinion. Dea is Muslim and Matea is Croatian, but both agree that people are eager to move on. "Some older people have raised their children not to interact so much with people of other religions, but I don't judge people for that," says Matea.

Paradoxically, it is the dysfunctionality of the system that makes it difficult for Bosnia to join the European Union. It has been 22 years since it became a "potential candidate" for the European club. And it wasn't until 2022 that it officially obtained the status. While Brussels leaders have spent years looking the other way and delaying the accession of the Balkan states, other powers such as China, Turkey, and the Gulf countries have tried to fill the gap. In fact, more flights to cities in the Middle East leave Sarajevo's small airport than to other European cities.