Why is the Spanish economy competitive but less productive?

The trend has been towards a model of investment in low added value activities that allow for more sales abroad but redistribute growth less.

BarcelonaIt's one of the essential issues for an economy: increasing productivity, which translates into true progress. And the Spanish economy lacks that leg to gain quality, as reflected in the investment data as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP), which is below the European average. However, it is competitive, as shown by the trade surplus data, that is, it earns more from what it sells abroad than what it pays to import. The opinion group EuropeG, co-directed by former Minister of Economy Antoni Castells and Professor Josep Oliver, has focused its new debate on this subject based on a study by Joan Ramon Rovira, head of research at the Barcelona Chamber of Commerce.

The fact is that, according to this expert, the capital stock per employee is more important than the percentage it represents of GDP, which is a flow. In short, "how and what is invested is more important than how much," and examples include Japan, the United States, and the so-called EU-5 (Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, and Belgium). Rovira emphasizes the Spanish economy; during the first decade of the century, significant investment was made "in unproductive assets." The Chamber's research director states that competitiveness is given a lot of priority because the term productivity is seen as "abstract," but in the long run, it is found that it "determines the standard of living" through GDP per capita, that is, the division of the pie.

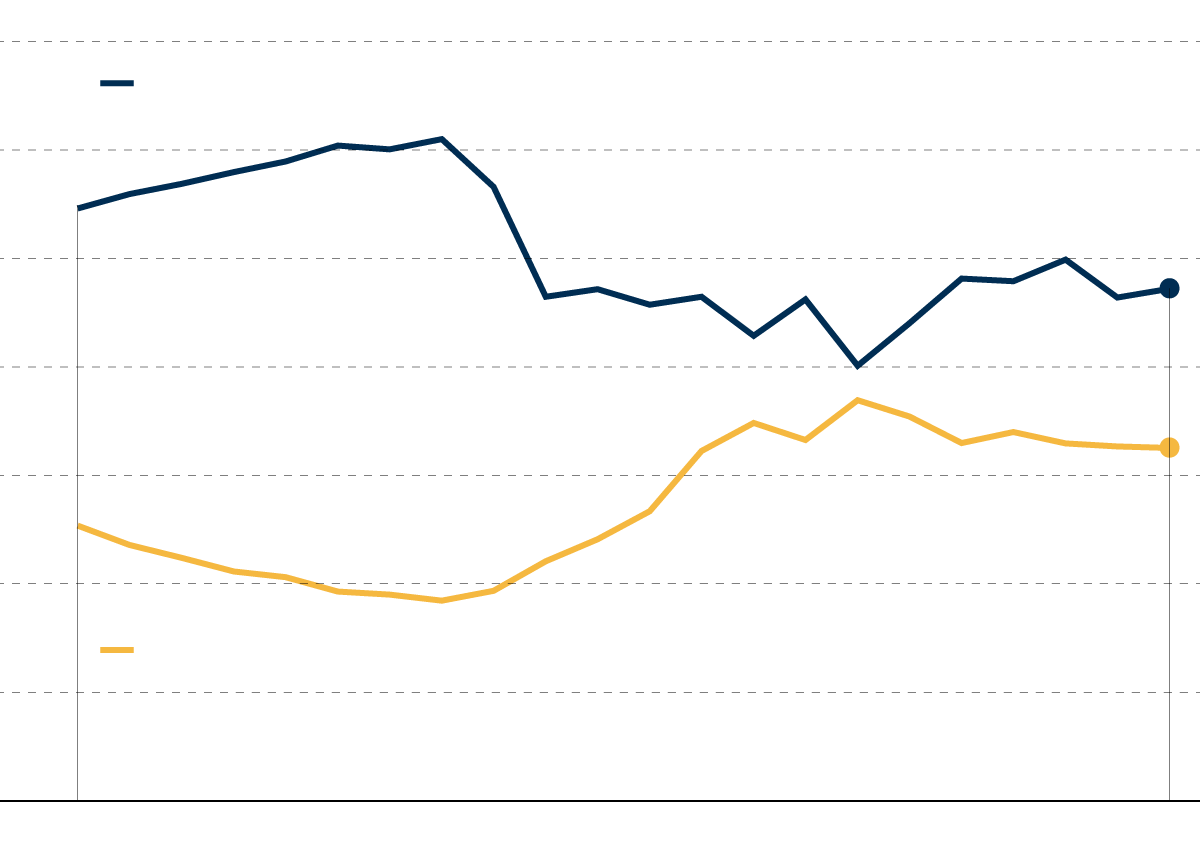

In any case, as a result of the investment strategy in Spain—a similar pattern is replicated in Catalonia—capital productivity fell, and during the second decade it stabilized but did not improve. In the Spanish case, capital intensity is high, "but with a low capital endowment per employee (low labor productivity)." One of the distinguishing features is a lower level of technological progress in the labor sector; and in the capital sector, the sectoral composition, "with a preponderance of activities with low intensive assets that transmit technical progress." In short, "the concentration of investment in low value-added sectors."

The conclusion is that the Spanish economy has been built "on a pattern of specialization in low- and medium-technologically intensive activities, which in part tends to be self-perpetuating." Instead, it should seek to exploit its competitive advantages in areas such as "energy, food, mobility, health, and creativity (from fashion and design to architecture) with established business ecosystems that can play a driving role in the transformation toward increasingly knowledge- and technology-intensive activities." One of the main recommendations is that political authorities should promote transformative investments in the most competitive areas and with "a specialization pattern more focused on increasing GDP per capita than GDP as a whole."

Productivity is a matter of concern. This was expressed by the former Ministers of Economy who participated in the Fourth Congress of Economy and Business last week in Barcelona. These included Antoni Castells (PSC), Pere Aragonès, who later also served as President of the Generalitat (Catalan Government), Natàlia Mas (ERC), and Jaume Giró (Junts), although the latter placed more emphasis on competitiveness and issues such as bureaucracy, taxation, and absenteeism. The Círculo de Economía (Economic Circle) has also formed a group of experts coordinated by economist Xavier Vives to seek solutions for improvement with a three-year perspective.

However, data from the Statistical Institute of Catalonia (Idescat) includes some more positive figures. Last year, total factor productivity grew in Catalonia by 1.8% compared to 0.7% the previous year. Breaking down the data into the variables included, labor productivity increased by 1.2%, compared to 1.5% in 2023; and capital productivity repeated a rise of 0.5%.

The opinion group, which also includes economists Martí Parellada, Vicente Salas, Rafael Myro, and Gemma Garcia, proposes economic policy guidelines "aimed at strengthening the formation of productive capital" and highlights the crucial role of public policies, along with business strategies, in accelerating productive growth. It also advocates for industrialization in construction, greater professionalization in the hospitality industry, and a more intensive application of digitalization in retail. It also emphasizes the need to successfully address the challenge of training, retaining, and attracting talent by promoting vocational training and implementing measures to reduce the school dropout rate.

It also proposes simplifying administrative processes that, in its words, hinder business dynamism and demobilize investment," and points out that the public sector "must proactively commit to facilitating, promoting, and, where appropriate, complementing all investment projects with an industrial focus, a long-term horizon, and that are aligned with strategic objectives.