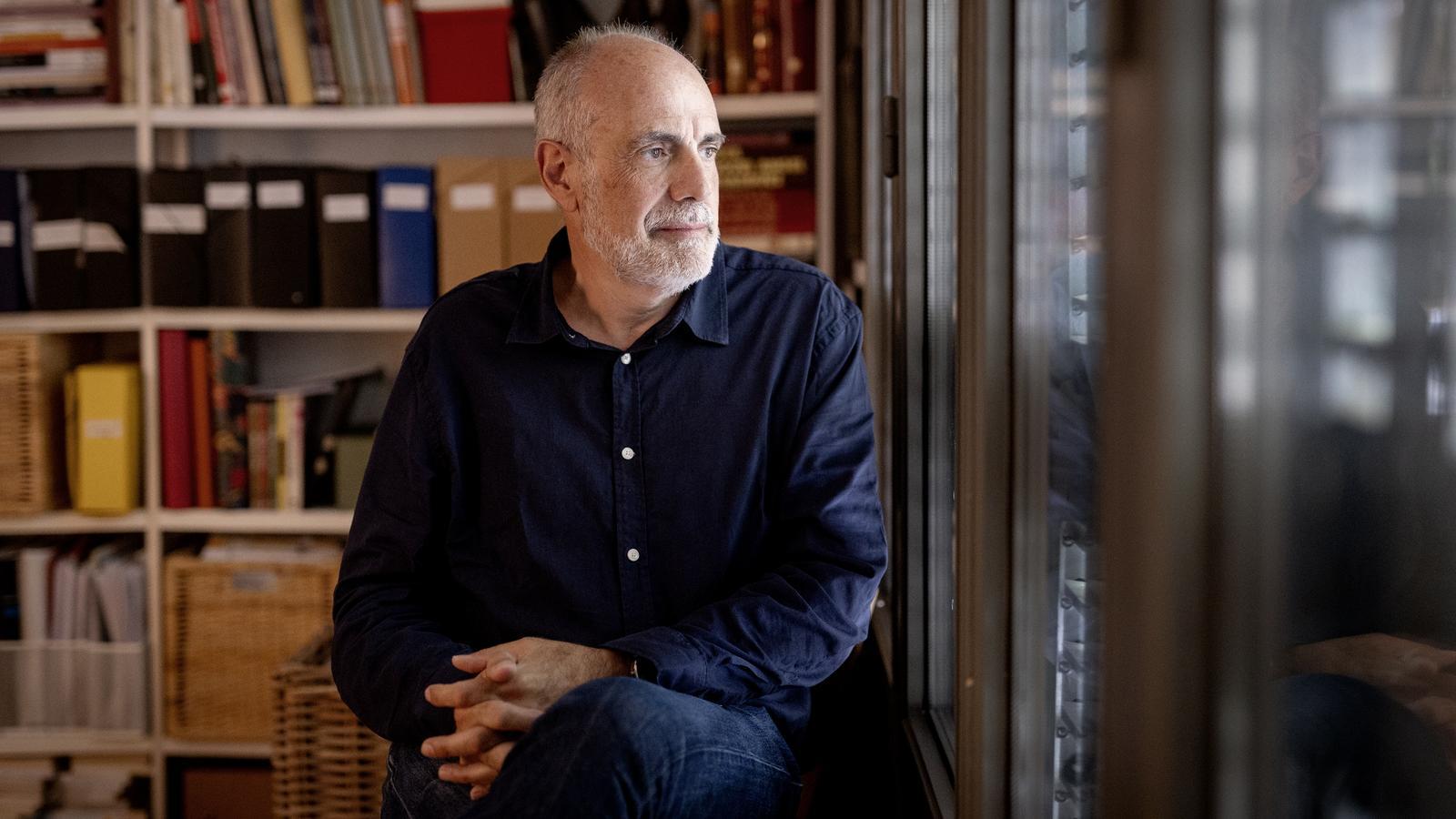

Joan Ridao: "The Statute and the Process have taken a generation of politicians feet first."

Parliamentary lawyer and author of the book 'Parliamentary Law of Catalonia'

BarcelonaJoan Ridao (Rubí, 1967) is currently a lawyer in the Parliament of Catalonia and has just published Parliamentary law of Catalonia (Atelier Llibres Jurídics, 2025), a compilation of Catalan parliamentary law. However, he had also previously been involved in politics: he was a member of the Catalan Parliament and Congress for the ERC (Republican Left), as well as president of the Institute for the Study of Self-Government.

Why was a parliamentary law manual necessary in Catalonia?

— There wasn't one. Neither now nor during the Republican era. Until now, there has been no work that synthesizes not only positive law but also other factors that have mediated Catalan parliamentary law, such as customs, laws, or the intervention of the Constitutional Court. The reason for this omission is that Catalonia has never had a state. In 1714, two towers also collapsed, as in New York: public law, its own institutions, and the public treasury. Only private law remains.

What specific features might Catalan parliamentary law have compared to what is done in the State?

— The main contribution of Catalan public law to the history of humanity is the Generalitat of Catalonia. When it was founded in 1359 in the Corts of Cervera, it was what is known today as the permanent deputation, which oversaw the powers of the chamber when it was not in session. That said, during the democratic-autonomous era, parliamentary law did not differ much from that of the Corts until 2005, when, with the approval of the Statute, modern regulations were also introduced, eliminating the vestiges that still exist in the Congress and Senate of prioritizing government stability. In Catalonia, counter-majoritarian regulations were implemented, as minorities can, for example, request a commission of inquiry, a special plenary session, or an appearance by the president.

How can we combine the inviolability provided for in the rules of procedure—that is, the protection of freedom of expression in parliamentary seats—with curbing the far right when it launches hate speech from the rostrum?

— This concept of parliamentary inviolability arose in 17th-century England, when the king could order the arrest of a member of parliament simply for speaking ill of him or voting against his interests. And today it has a modern meaning: it prevents a political opponent from being falsely eliminated for potential slander or insults. While there are no absolute rights, Strasbourg has affirmed that this right to freedom of expression for parliamentarians is even more limited than that of others, even with the right to offend. The limits are not to attack certain minority groups, to prevent antisemitic expressions against the Roma people...

But, in the wake of far-right rhetoric, the option of sanctioning interventions in parliamentary buildings through the Code of Conduct has emerged. How does this relate to the current immunity?

— It's not a simple matter. The fact that freedom of expression is broad in the political sphere doesn't mean that the power to moderate the debate, which falls to the chairperson of the session, cannot be exercised. A member can be called to order or even excluded from the plenary session. There is another mechanism, Article 7 of the Code of Conduct, which refers to the role of the member as an exemplary leader. If a violation is deemed to have occurred, a letter is sent to the Bureau and the Committee on the Status of Members, where it is considered whether the member should be sanctioned for violating the Code of Conduct. This is not a bad solution, as it offers greater guarantees and the chairperson does not act alone, but it is not definitive.

And do you think the number of deputies should be maintained?

— It's an issue that has received bad press, to the point that many statutes have been amended to eliminate it. However, it presents advantages and disadvantages for those convicted. While they enjoy greater protections when tried by a collegiate body, they also have the disadvantage of not being able to appeal to another criminal court.

Don't you think it's a privilege, then?

— A member of parliament who must be tried in the High Court of Justice of Catalonia or the Supreme Court has no right to appeal; however, those tried in a criminal court have two instances. However, one cannot go against a trend that seems to be the majority and could be eliminated.

Strasbourg is wondering whether Parliament can discuss everything.

— Yes, the latest ruling [upholding the Constitutional Court's veto of self-determination] was a cold shower. However, I am convinced that the Constitutional Court will gradually reestablish its doctrine. Before the Trial, only acts with legal effects could be reviewed, and everything changed in 2014 when, with Parliament's declaration of sovereignty, the Constitutional Court unusually overturned it, stating the following: The legal aspect is not limited to what is bindingWe advocate that the parliamentary committee not act as a mini-TC and that debate be allowed in plenary.

The Parliament's rules also provide for suspension for corruption, as occurred in the case of Laura Borràs.

— This is a peculiarity of the regulations that appeared in 2017, and I have already argued that it is unconstitutional, as it does not involve a corruption crime, but rather different types of crimes, and therefore lacks specificity. At the same time, the decision falls to the board of directors (which is a management body), and there is no guarantee procedure as in other sanction cases. I believe it is poorly executed.

Should the legislative procedure be reformed?

— The committee recently reached an agreement to streamline the legislative process, but for me, something structural is needed. What prevails in the chambers is still the dogma of the three readings, conceived at the end of the 19th century. It makes no sense that the legislative procedure in Parliament is now so rigid that it could irritate or provoke exasperation. There needs to be a comprehensive rethink. For example, in Congress, they have empowered committees as full legislative venues; this is also provided for in Parliament, but it is not used. The idea would be to start the process in the plenary session and have it approved in committee [without returning to the plenary session]. Another measure that can be taken is to set a limit on the number of hearings that can be requested. And the legislative process must be rethought, not only in Parliament but also in the Government, where there must be a reduction in procedures and deadlines.

Nowadays, the government usually issues decree laws to avoid the entire process.

— There is an abuse of decree-laws. The urgency must be justified; the problem is that the Constitutional Court adopted a very deferential attitude that is now being corrected, as is the Council of Statutory Guarantees. Decree-laws must be justified by the urgency.

Parliamentary motions, interpellations... should parliamentary oversight also be reformed?

— There is a certain trivialization of these initiatives, as these mandates to the government are not enforceable before the courts. They must be used effectively, with clear, concise, and forceful mandates, and their compliance must be guaranteed. The regulations also include mechanisms to assess their compliance.

Have you seen many representatives come and go? Is there a higher or lower level than the previous one?

— The older generation always says that the past It was better, but it's true that if we think about the founders of the European Union, they are no longer on the same level. In the case of Spanish and Catalan politics, a similar conclusion can be reached. However, in the Catalan case, there is an added element: both the reform of the Statute and the Process have brought in a relatively young generation of politicians with an advantage. This is a differentiating factor compared to Spanish politics. Third parties have had to emerge because the Spanish judicial system has unfairly used coercive measures that have seriously damaged the quality of Catalan politics.