"...when suddenly, from the sky, where they say angels and birds come from, a downpour of fire fell, heaven was hell, order had been reversed"

It was market day, Josep Palau i Fabre

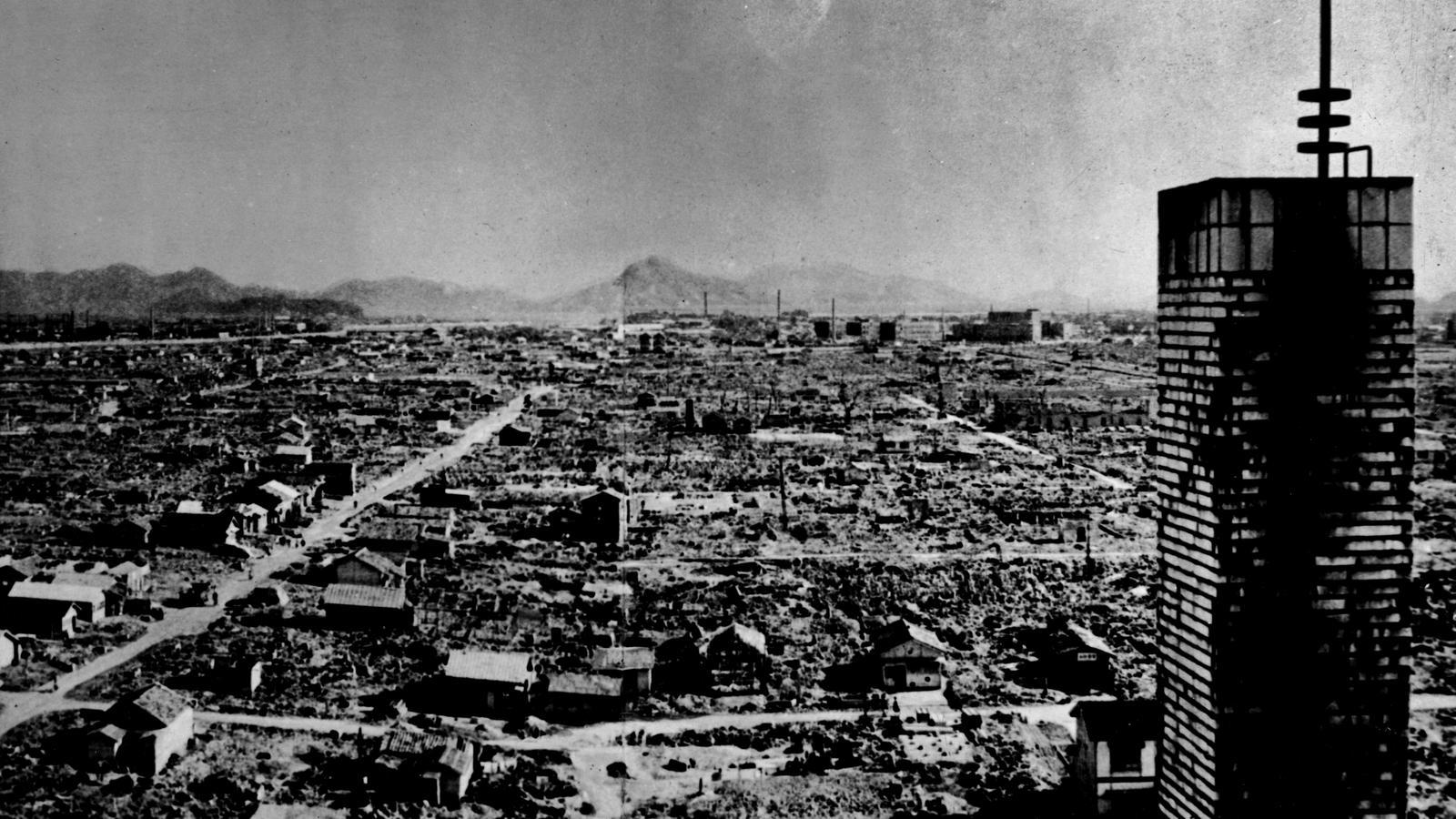

Today, Wednesday, when you open the newspaper, it will be just eighty years since theEnola Gay launched the Little boy, the first atomic bomb against a civilian population in history. It was dropped on the city of Hiroshima, which was reduced to fire, shredded to rubble and iron, causing 140,000 deaths and beginning the era of nuclear horror. The next day, the image of that mushroom A 4,000-degree blast circled the globe and still does today. Just three days later, on August 9, Truman insisted and the plutonium bomb Fat man, launched from the Bockscar, dumped the same munition on Nagasaki, causing 70,000 deaths. It was the second nuclear bomb in history—and since then, the last to date, with as many Dantesque consequences as it left. Then came the black rain, thousands more deaths, decades of radiation, and illnesses that still linger. Just a few months earlier, lest we forget, Dresden had also been devastated by British and American aircraft using non-nuclear weapons—25,000 dead, and even Churchill expressing doubts about the attack. In none of the three cases—despite the avoidance of greater evils maintained by their apologists—is it at all clear that it was necessary: German surrender was not far off, and Japanese capitulation was imminent. But it was August 1945, and the unfortunate wake of the German bombing of Gernika was already in the offing. And from the saturation bombings of Barcelona that so excited Mussolini in 1938. In the collapsed city where bombs rained down, it was then saved by the Barcelona subsoil—the same subsoil we walk on every day, that still saves us without realizing it and where 1,300 still survive. Hiroshima and Nagasaki, eight decades later, are still saved by the patient, peaceful resistance of the four ginkgos that survived, those four trees that sprouted again, and especially by the voice and the silence speaking of the hibakushaThe survivors. Those who will remember today, calling for effective global nuclear disarmament, that on that morning eighty years ago, all the clocks of life perished and stopped, burning, at eight-fifteen and seventeen seconds.

On that August 6th, the technical man, the Promethean man with a zeal and a God complex, achieved the option of annihilating humanity in a single blow, the aporia of mutually assured destruction and the nihilistic feat, so often brought to cinema, of the Final Solution. History tells us that after the first successful military test in the American desert of Los Alamos, Oppenheimer recited a traditional Indian saying: "I am now death, the destroyer of worlds." Less often said is that the soldier standing next to him retorted: "What we really are is a gang of sons of bitches." What separates 3,000 meters of altitude from 100,000 deaths? A single industrial button. What preceded—Hiroshima and Nagasaki—Major Thomas Ferebee and Captain Kermit Beahan, respectively. Needless to say, for having murdered more than 200,000 people, they were never tried but treated as heroes. They didn't even repent. But as there is always another story, we will have to look for it. And remember, for example, the late Howard Zinn, author of the essential The bomb: he was one of the young American pilots who, from up there, dropped napalm on Europe, who revisited its effects years later and, as an epiphany against nuclear horror, became an unavoidable anti-war intellectual for us. Or the counter-story of the pilot Claude R. Eatherly, driven mad by pain and haunted by guilt until his psychiatric confinement, with whom Günther Anders corresponded until he published The Hiroshima pilot, where former pilot, victims, and intellectuals conspired against future disasters. Anders, a philosopher critical of technology who maintained that Eatherly we could be anyone, also wrote in 1958 The Man on the Bridge. Hiroshima and Nagasaki Newspaper, in the unbeatable Catalan edition of Club Editor since 2023. In any case, since 1955, the Russell-Einstein Manifesto, which also turns 70 this year, still asks us: "Do we want to end the human race or should humanity renounce war?" Meanwhile, Kiev burns, the Donbas smokes, and Gaza succumbs.

Today, 80 years later, in the midst of the escalating war and sordid submission to Trump in economic, energy, and military matters, we have seen how the nuclear issue has been rekindled in recent months—the attack on Iran, the submarines sailing through the waters, North Korea's nuclear tests, or the Zaporizhia nuclear plant. But the worst thing, according to SIPRI in Stockholm in its latest report from June, is that the nuclear arsenal has not stopped growing again, after the decline following the Cold War, and has entered into a new rhetoric of threats and a dangerous arms race of expansion and modernization. Today, 9 states have 12,241 nuclear warheads, some with a destructive power 20 times greater than that of Little boy, which would be capable of destroying the world a thousand times over—and even though one is enough. Ninety percent are in American and Russian hands. Paradoxically, criminal cynicism at the helm of international politics, which also has a nuclear stockpile and does not report anywhere and is not subject to any international inspection, is Israel, which has 90 nuclear warheads, ready to be used in the event of an "existential threat." Israel, the only state to have bombed five countries in the last year. Meanwhile, it also turns out that the most progressive government in Celtiberian history has still not signed the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons, already signed by 94 states since 2021. Let them save their words today until they back it up with actions tomorrow, when the only way to avoid it becomes possible.

And yes. Like the retina of the eye of the girl fleeing napalm in Vietnam, we have seen Gernika repeated a thousand times—Saigon, Sarajevo, Fallujah, Grozny, Baghdad, Rojava. And as Santiago Alba Rico hones with his unarmed lucidity, maintaining that in reality we have not survived Hiroshima, it should be added that the 1945 model that is now faltering pivots on a frightening double standard. In an abyss that completely separates Nuremberg from Hiroshima. Because while the horizontal extermination of the lager Germans, from the Nazi concentration camp universe and the bottomless pits of extermination in the camps, at the same time vertical extermination was absolved of all the crimes of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. As if killing from the air were less criminal and more aseptic than doing so from the ground, and aerial crimes, in the clouds of impunity, left precarious terrestrial law in suspense. What we also know, eighty years later, is that Israel has already dumped 100,000 tons of bombs on Gaza, that 90% of the territory is already rubble, hell, and hunger, and that 60,000 Palestinians have died—93 a day, 4 an hour, one every fifteen minutes. And so many still resisting naming it by its name: genocide. Which would not be possible, invariably, without so many silent complicities: the hard, the soft, and the same old ones. As if Gernika were still burning. As if we had never survived Hiroshima and Nagasaki.