A river of despair where Syrians flee sectarian violence

Thousands of Alawites march off the Syrian coast following attacks by radical Islamist militias.

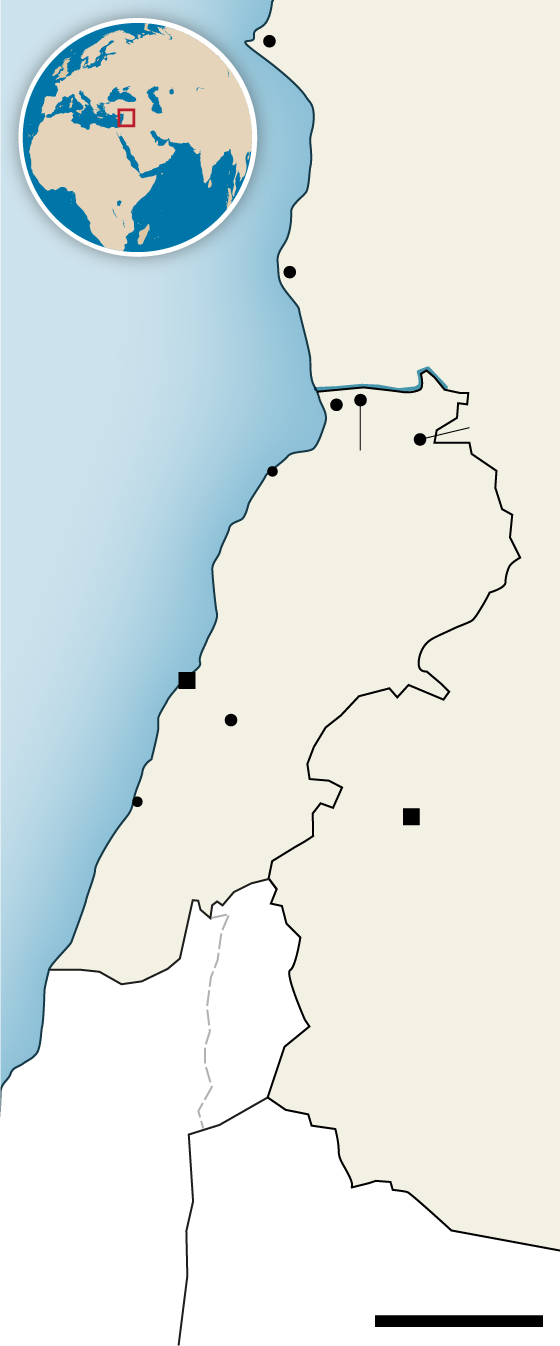

Al Akkar (North Lebanon)A steady stream of Syrian families is flooding the Nahr al-Kabir River, the natural border between the Syrian coast and northern Lebanon. Exhausted after several days on foot to circumvent the checkpoints imposed a week ago by security forces, they are crossing through areas where the water level is lower. and flee sectarian violence perpetrated by radical Islamic militias against the Alawite minority, to which the Al Assad dynasty belonged.

Among the newcomers is Fatma, with her husband and two children. Her skirt soaked, shoes in hand, she struggles forward, her feet sinking into the mud. Before continuing, she stops and turns back, looking exhausted but with a sense of relief. "We were afraid they would attack us at any moment. So we decided to go to our relatives' houses in Lebanon until things calmed down. We've lost so many things... We left our house and everything we had behind, and we simply ran away."

Others, like Fahed, have nowhere else to go. He comes from rural Tartus. Although Ahmed Sharaa's government has declared victory over the insurgency in Latakia and Tartus.The violence hasn't ended for those who still feel the hatred in their necks. Fahed speaks of Islamists imposing their own justice, of executions at dawn, of nameless bodies in the streets. Then, he takes out his cell phone and shows, he says, his brother's body, decapitated, lying at the door of his house.

The reception spaces, overcrowded

With nothing but the clothes on their backs, he and his wife will walk another six kilometers to seek shelter in the first villages of the Al Akkar municipality. But there is barely any space. In Massoudiyeh and Tal el Bireh, predominantly Alawite villages, residents have opened their homes in solidarity with the Syrian refugees. Some municipal buildings and mosques also serve as shelters, but they are overcrowded.

"We have received more than 10,600 refugees, and they continue to arrive every day," warns Abdelhamid Sakr, a local leader in Tal el-Bireh. "We have the support of the Red Cross, but we hope that our government will take this matter seriously and address the needs of our Syrian brothers." The municipal headquarters, now crammed with mattresses and defeated faces, has become a temporary shelter for fifty families.

Mohamed, an Alawite from the Syrian city of Hama, arrived with his wife and five-month-old baby last Friday. They are now taking refuge in the cramped lobby of the government building. While he drinks mate and lights one cigarette after another, he watches the baby sleep, covered with a blanket on the cold floor. "Conditions are not good here. We don't know how much longer we'll have to stay. We won't return until security is restored. They want to finish us off. They've massacred women and children," he says, his voice breaking.

Beside him is Hussein, a former soldier in the Assad regime, who explains that the new administration has issued identity cards marked "former official" of the former government. "It's a trap. Showing your ID is like sentencing yourself to death. The Islamists set up checkpoints and asked for identification. I had to flee at night on foot to avoid the fate of other former Alawite soldiers."

The other face of persecution

Lebanon is facing a new wave of Syrian migration. Trapped in a relentless economic crisis and its aftermath from the recent war with Israel, his government is barely holding on. History, cruelly repeating itself, drags the same shadows as in 2012, when hundreds of thousands of Syrians crossed this border fleeing Bashar al-Assad's repression. Now, the harassment comes from another face, another power, but with the same brutality.

Several kilometers away, the Massoudiyeh Mosque has opened its doors to refugees. Women and their children sleep downstairs; men sleep upstairs. There we meet Isa Youssef Wannous, a Syrian from Latakia, who is organizing mattress distribution and aid donations. His energy is overwhelming, but what is most surprising is his steadfastness. During the conversation, he shows a photo of his daughters, ages six and eight. "I haven't heard anything for ten days," he says. When clashes broke out between militias loyal to Assad and Islamist groups arriving from Idlib, he tried to flee with his wife and daughters. He went to look for the car while they waited for him on the street. Suddenly, a white van appeared. Hooded men got out and took the girls away. "I'm trying to find out where they are, calling all my contacts, but there's been no luck," he explains with a worried tone.

After fourteen years of civil war, Syria remains a powder keg where violence distinguishes neither sides nor innocents.The drama of the displaced is not only a desperate exodus, but also a symptom of a deeper crisis that remains unresolvedIn Lebanon, although authorities assure us that the situation is under control, the constant flow of displaced people threatens to upset the fragile balance. What is most worrying is not only the humanitarian crisis, but also the risk that the sectarian violence that is rife in Syria could spill over the border and fuel internal tensions in a Lebanon already plagued by instability.