Could Norway's large rare earth deposit represent a turning point for Europe?

The mining project presents economic, environmental and geopolitical uncertainties

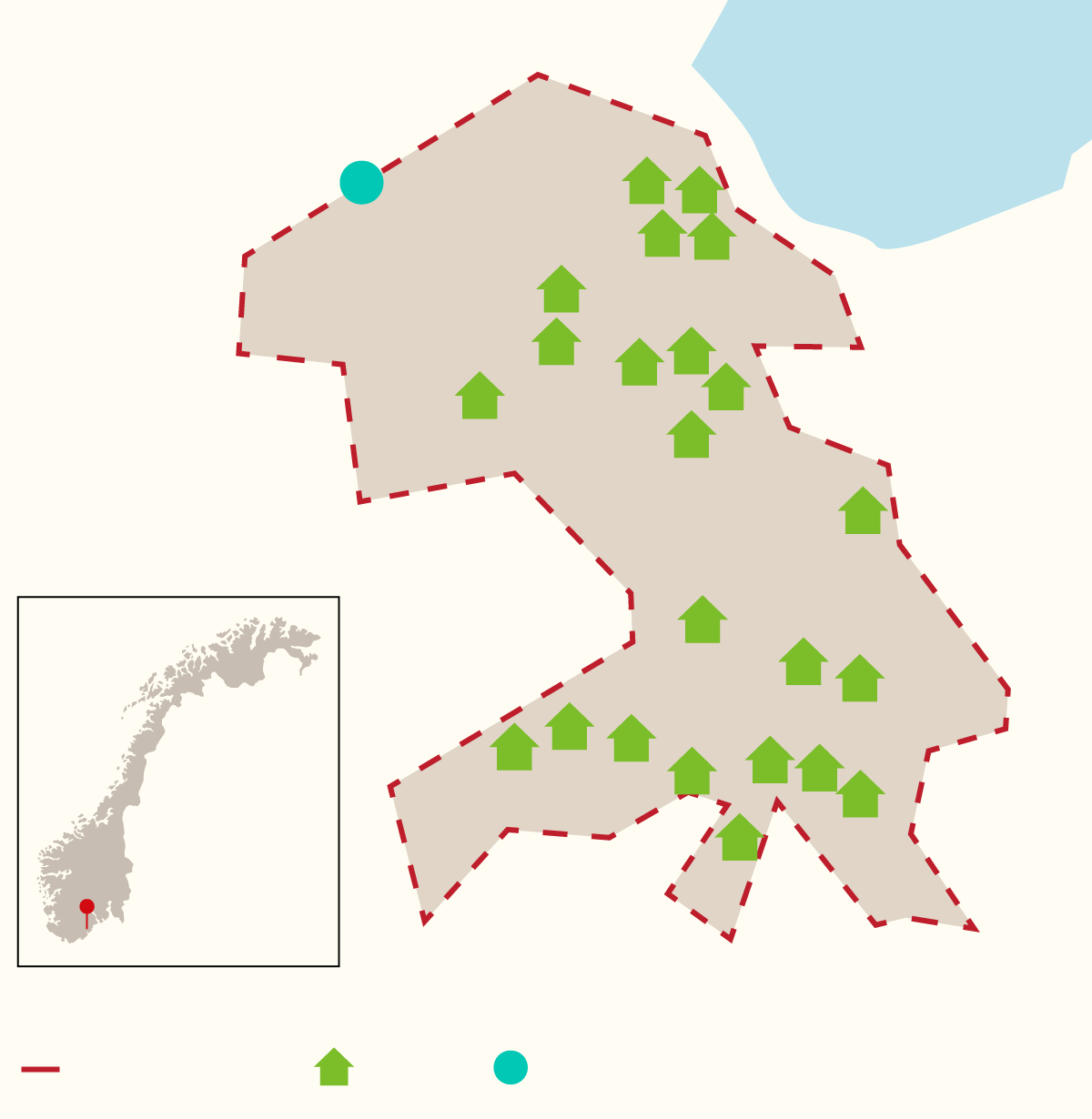

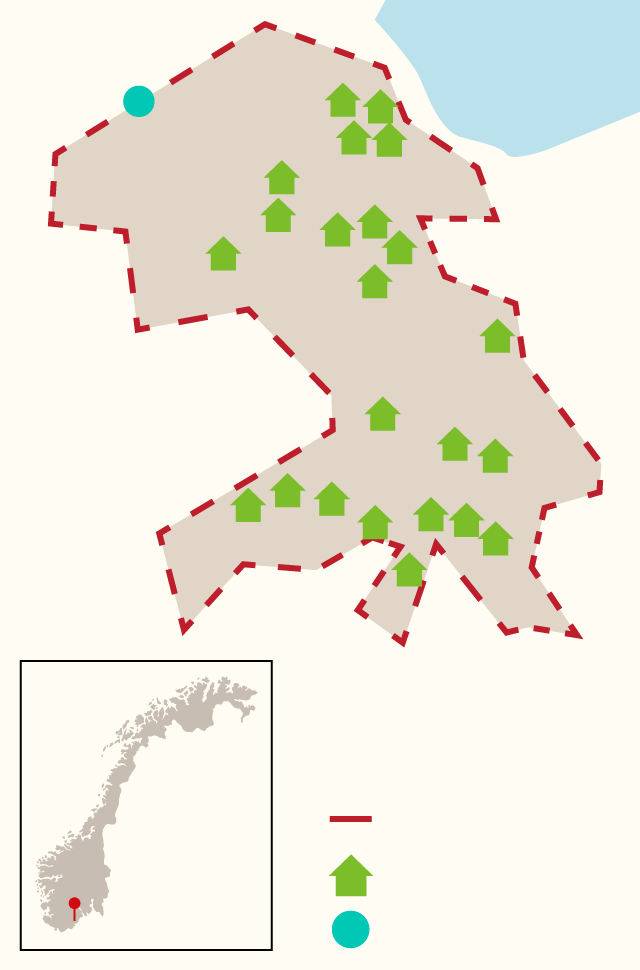

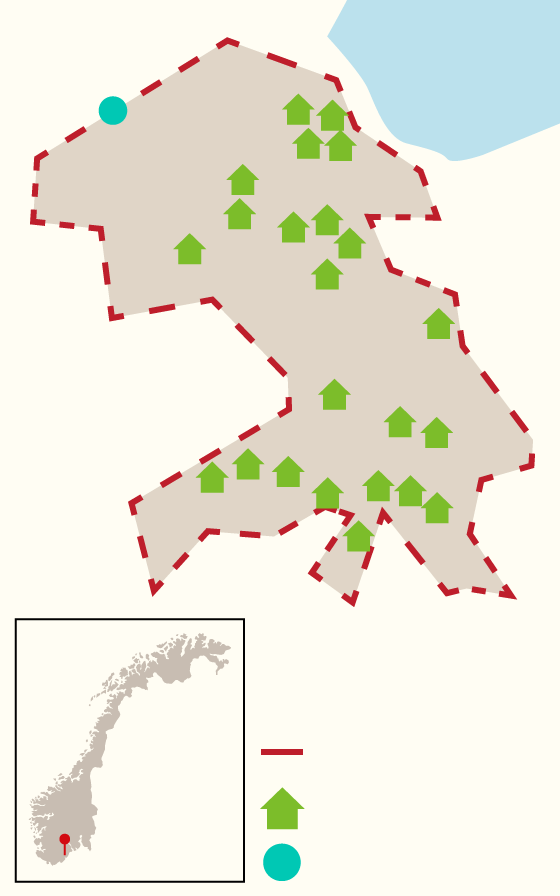

BarcelonaUlefoss, a former mining town of 2,000 inhabitants in southern Norway, could represent a geopolitical turning point for Europe. Mining company Rare Earths Norway (REN) has identified a 9 million-ton rare earth deposit, placing the town on a similar scale to the world's largest active mines in China and the United States.

Rare earths are a group of 17 chemical elements essential for digitalization and the energy transition, because they are essential in technologies such as solar panels or electric vehiclesThey are usually found in very low concentrations and mixed with other materials, making their extraction very expensive, requiring large amounts of energy and water, and generating large amounts of waste. Furthermore, they are often mixed with radioactive elements such as uranium and arsenic, which are hazardous to human health and the environment.

For now, the main European problem is the strategic dependence on China, which extracts 70% of rare earths and processes 85% in 2023 Beijing imposed restrictions on exports of some of these elements, which it extended this April.

Faced with this situation, the European Union has legislated to ensure a secure source, because for now it does not have an internal source of rare earths. 2023 passed the EU Critical Raw Materials Act, which sets the goal that by 2030 at least 10% of European demand for these materials will be extracted within European territory and that no more than 65% will come from a single third country.

In this regard, REN aims to supply a third of Europe's demand for rare earths. While Norway is not a member of the EU, it is considered a "faithful" ally of the Union, with strong trade ties. Norway, for its part, has also implemented regulations in this direction, and in 2023 the government presented its mineral strategy, which aims to develop the "most sustainable" mining industry in the world.

A controversial project

However, the project raises numerous questions about its viability. For starters, the deposit located by REN is located beneath residential areas and a school. However, so far, the idea of a future mine has not generated major objections from the population or local authorities, likely due to the fact that Ulefoss is one of the oldest mining communities in Europe—there were already iron mines there in the 17th century. However, some residents complain that some of the explorations carried out by REN are being carried out in ponds, which could disrupt the natural balance of the area, according to DW.

The main problem facing the mining project is the risk of subsidence, that is, the ground sinking into the empty space left by the drilling. This has already happened in Kiruna, in northern Sweden, a town that had to be permanently relocated at the beginning of the century. To prevent this, REN wants to plug the holes left behind by using half of the waste generated by the mine, mixed with a binding agent to strengthen the rock.

Furthermore, to avoid affecting the town's residential areas, the company is proposing the creation of an "invisible mine," which will begin drilling diagonally 4 km from the town center. But Alfons Pérez, an energy and climate researcher at the Observatory of Debt in Globalization (ODG), points out that "the modalization process can handle anything, and then things get much more complex" and that this project will significantly increase the costs of the materials extracted: "Rare earths from China will be infinitely cheaper." Furthermore, it must be taken into account that technological innovations of this magnitude require very high energy consumption, and it is estimated that the Ulefoss mine, as planned, would consume around 1% of Norway's annual energy consumption.

Despite concerns, REN hopes to begin a pilot operation next year and have the mine operating at full capacity by 2030. Pérez has different estimates: "Taking into account prospecting, investments, evaluations, and permits, the average time to extract a ton of rare earths is around 16 years." He explains that these types of projects are difficult to implement because they require a significant initial investment and returns don't arrive until 10 or 15 years later. "Of the proposals that are made, perhaps 1 in 10 are successful," he adds.

A geopolitical shift?

Regarding the geopolitical significance of the potential future Ulefoss mine, the ODG scientist warns of caution: "No matter how much we increase extraction in Europe, China has new projects underway, and its rare earths will continue to become cheaper"; even more so considering the technical difficulties posed by the REN mining project.

Thus, presenting European extraction as a solution to dependence on foreign powers may be fallacious. Experts warn that many of the rare earths are destined for highly controversial industries such as the arms industry and they assure that you can choose alternatives such as recycling –recovering rare earths from electronic components they already contain– and rationalizing demand.