The wars behind rare earths and critical minerals

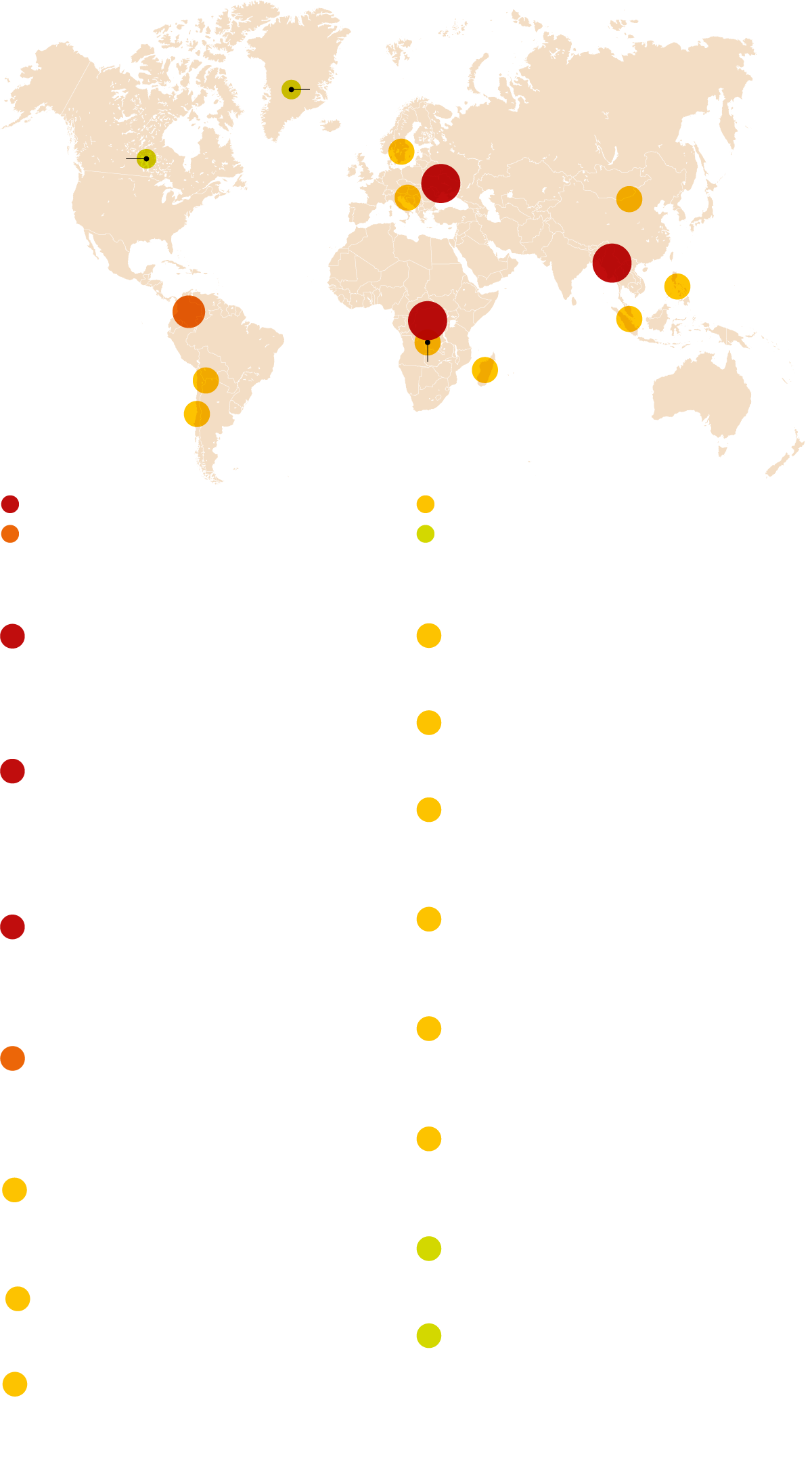

Minerals such as lithium, rare earths, and cobalt fuel conflicts such as those in Ukraine, Congo, and Myanmar, but also generate social and environmental disputes around the world.

BarcelonaUkraine's rare earths could be the key to unlocking a future peace agreement, following the agreement signed this week by the Donald Trump administration and Volodymyr Zelensky's administration. The United States' hunger for these metals and other critical minerals, such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, and tantalum, is at the heart of its involvement in the war in Ukraine, but also the reason why Donald Trump is threatening to annex Greenland and Canada. But the United States is not the only power immersed in the rush for critical minerals. The European Union has also defined as a strategic priority "achieving a secure and sustainable supply chain" for 34 critical raw materials, which include these and other minerals. essential for green technology and digital, but also, and now more than ever, for the growing military industry.

Currently, China practically monopolizes the market for 19 of these 34 minerals. The desire of other world powers to break their dependence on Beijing has opened a race for critical minerals that fuels armed, social, and environmental conflicts in countries—mostly in the Global South—that have reserves of these minerals.

Ukraine

Ukraine holds 5% of the world's total mineral resources: it has reserves of 22 of the 34 critical minerals classified by the EU, according to data from the Kiev government. In addition to titanium, gallium, scandium, manganese, kaolinite, iron, graphite, and uranium, it has untapped deposits of lithium and rare earths. The problem is that a large part of these reserves are located in territory occupied by the Russian army or in deposits that are still undetermined. "The maps of these reserves date back to the Soviet era and are likely overstated," notes Emily Iona Stewart, head of transition minerals at Global Witness. The agreement between Kiev and Washington, which will allow the United States access to 50% of the profits extracted from these Ukrainian minerals (as well as gas and oil), in exchange for its mediation with Russia for a peace agreement, is one of Kiev's trump cards in the negotiations. But it's also a threat to Russia, which controls 20% of Ukraine's territory, where rare earths, titanium, and lithium are also found, and which has reserves on its own territory: it is the world's leading producer of palladium.

The coltan war

The negotiation of the agreement with Ukraine gave the Congolese government an opportunity to win its own war. Last February, the president of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), Félix Tshisekedi, sent a letter to Donald Trump offering him access to his country's vast reserves of critical minerals in exchange for military aid to defeat the Rwandan-backed M23 paramilitary group. This rebel group currently controls the country's main coltan mine, the Rubaya mine in North Kivu province. The advance of the M23, which now controls the provincial capital, Goma, and part of South Kivu, was made possible thanks to the assistance of the Rwandan army, "one of the most powerful in Africa, equipped with high-tech military equipment," explains Josep Maria Royo, an Africa specialist at the UAB School for a Culture of Peace.

"The origin of this conflict is not minerals, but they have contributed to feeding the combatants and prolonging the war," he warns. The UN has documented the presence of 4,000 Rwandan soldiers in Congolese territory, despite the Rwandan government's denials. And, once again, the greed for metals that fuels these conflicts is not only the United States's. Last year, the European Union (EU) signed an agreement on cryogenic minerals with the Rwandan government, "a country that has no minerals" and is extracting them from the DRC, something that "is perpetuating the conflict," Stewart explains. The European Parliament itself voted on a resolution last February calling on Brussels to suspend the agreement, designed to contribute to the European supply of tantalum, tungsten, gold, and niobium, with "potential for the extraction of lithium and rare earths," according to the EU itself.

The Cobalt Slaves

In the south of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), there is no war, but cobalt mines generate another type of conflict: child labor, semi-slavery, pollution, and human rights violations. This region of the DRC contains 60% of the world's cobalt reserves, which are exploited mainly by Chinese companies. Unlike coltan, cobalt can be extracted by hand, and this has led to the spread of the so-called "cobalt mining industry." artisanal mining, where a very impoverished population, including children, excavates to remove the mineral treasure and sell it in exchange houses (mostly also controlled by Chinese companies) for one or two dollars a day.

The invisible war

Rare earth mines in Kachin province in northern Myanmar are fueling the clash between The Burmese military, which seized power in the country in a coup in 2021, and the region's militia, called the Kachin Independence Army (KIA). The country has been immersed in a civil war since the coup, but in that region the conflict dates back much further due to the resistance struggle of the majority ethnic group. In recent years, mining operations controlled by the military junta and its allied paramilitary groups have multiplied, as have those controlled by the KIA. "The impact on the health of workers, the environment, and local communities remains horrific," warns a Global Witness report. In recent weeks, mines previously controlled by the military have fallen under KIA control. "We are waiting to see what changes this entails," adds Stewart. But in both cases, and in many cases of illegal extraction, the buyer of all these minerals is China, which has outsourced its rare earth production in this region of Myanmar: Chinese mining in Kachin is now double that of its own territory, according to Global Witness.

Potential conflicts

Donald Trump's expansionist ambitions threaten to generate new international conflicts whose main motivation is the rush for critical minerals. This is the case of Greenland, which Trump wants to buy or annex because he claims it's a "national security" priority. Ultimately, what he covets are its rare earth reserves, the largest untapped reserves in the world: the Kuannersuit deposit alone is estimated to hold 7 million tons of rare earths. Similarly, Trump's threat to make Canada the 51st state of the US also has a connection to critical minerals, because this neighboring state is not only rich in oil and gas, but also has large reserves of copper, nickel, lithium, and rare earths. In general, the entire Arctic is a region of potential conflict in this regard, because the melting ice caused by the climate crisis is opening up new trade routes and also new areas for the potential exploitation of critical minerals.

Armed groups and drug trafficking

In Colombia, it has been proven that armed groups still operating in parts of the country, such as the FARC and ELN, illegally exploit coltan and gold mines. Drug cartels also illegally exploit gold and copper. Furthermore, Colombia has lithium and nickel reserves, which, like gold, are generating social conflicts and resistance from local communities.

Local and indigenous resistance

Beyond armed conflicts, the rush for rare earths and other critical minerals is generating social and environmental conflicts around the world. To extract these minerals from the rock, highly polluting chemical processes are necessary. And some of them, such as rare earths, often appear accompanied by radioactive materials. In Malaysia, for example, there are no mines, but the rare earths Australia extracts from its subsoil are sent to this country for processing, and this has generated resistance due to the enormous pollution it leaves behind. In addition to pollution, the exploitation of these resources also generates the displacement of Indigenous and local communities, who have waged war in many parts of the world. The Global Debt Observatory (ODG) has documented up to 28 conflicts over rare earths around the world., from Madagascar to China, where the world's largest rare earth mine, Bayan Obo, is located, which has had a terrible impact on ecosystems and the health of the local population. But resistance is not only in the Global South: in Sweden, the country the European Union is looking to break its dependence on China in this field, there are also open conflicts over rare earth mines and other minerals that are affecting indigenous populations like the Sami.

"The European Union has committed to achieving 10% of the extraction of these minerals within its territory and 40% of the processing, with 25% coming from recycling, but by 2030 I honestly think that's very fair," explains Claudia Custodio, author of the study. In the lithium triangle of Latin America, formed by Chile, Argentina, and Bolivia, there is also local resistance due to the high environmental impact. "In Chile, we know the government is working to involve local communities in the processes and do things right, but in contrast, Javier Milei's government in Argentina, with its deregulatory agenda, is trying to sell lithium at the lowest possible price to the detriment of Indigenous rights," Stewart explains. He adds the Philippines to the list, where "there is violence against communities trying to defend their land against mining concessions."

Trump's hand in Serbia

Part of the huge social protests of recent months in Serbia has organized against a lithium mine owned by Rio Tinto.The country's courts halted the mining project due to environmental concerns, but the Serbian government is determined to exploit it and is even "holding talks with the United States" to exploit the key mineral, according to Stewart. The researcher claims that the Trump administration has leaked information to Serbia about the organizers of these protests, which it has had access to because they received funding from the dismantled foreign aid agency USAID, and this has led to the arrest of these activists. "USAID provided funding to many pro-democracy organizations in Eastern Europe fighting against Russian influence in the region, and now they've been stripped of it," Stewart warns.