10 years after the Paris Agreement: Who is still worried about the climate crisis?

The pact to curb global warming faces a resurgence of denialism just as it should be starting to bear fruit.

BarcelonaHugs, jumps of joy and applause greeted the ten years ago birth of the Paris AgreementIt had taken many years to bring it to fruition, and many hours of tense negotiations had been spent in the French capital during the COP21 climate summit. But on December 12, 2015, all the world's governments formally committed to preventing global warming from exceeding 2°C and preferably remaining below 1.5°C. The agreement was very imperfect—starting with the fact that it was not legally binding—but this historic milestone—getting 197 different governments to agree is a Herculean task—unleashed optimism: the fight against the climate crisis was finally an unavoidable global objective.

A decade later, the global context seems to have turned almost completely upside down. Climate change denial has returned, with louder voices than ever, and the fossil fuel industry is back in full swing. The threshold of 1.5°C above the pre-industrial average has already been exceeded, although only briefly in 2024 and not yet as a sustained average over a long period (which is what the Paris Agreement called for avoiding). And emissions of CO₂ and other gases responsible for the climate crisis, which were predicted to peak during this decade, continue to break records year after year. What is happening?

Emissions

"The effect of Donald Trump hasn't been felt yet; it will begin now, but what he's already doing is causing countries to slow down their climate action," says Olga Alcaraz, director of the Governmental Group on Climate Change at the UPC. The professor laments that the European Union is "following the lead" of the United States, to the point that it has struggled to reach the The COP30 climate summit, which begins this Monday in Brazil, is a major climate summit.with an agreed proposal. The meeting in the Amazon in the coming days comes ten years after Paris, and the world's governments are summoned with the duty to present a new (and ambitious) emissions reduction target for 2035. The EU is ultimately going with the same figure it had already put on the table in the past (a 66.5% reduction). agreement to cut emissions by 90% by 2040, but with many conditionstaxes imposed by states like Hungary or Poland. "This second term of Ursula von der Leyen has a much weaker climate agenda than her first. Back then (when she approved the Green Deal in 2019), the EU wanted to exercise leadership in the fight against climate change, but now the security agenda is much more important" due to the war in Ukraine. China, on the other hand, has taken the lead in the green economy and in the ten years since Paris has become a leader in renewables. "The Paris Agreement has something to do with it, but it doesn't fully explain it; what's happening is that China has seen this energy transition as a huge business opportunity and has jumped in headfirst: having a centrally planned economy, it has been planning each five-year economic cycle to promote renewables and now controls all the mineral resources of this industry," she points out. At its last plenary session last month, the Chinese Communist Party approved the new 2026-2030 five-year plan, which aims to "establish green production and a green lifestyle" so that "the peak carbon target is achieved as planned."

Beijing arrives at COP30 in Brazil with a promise to reduce its emissions by between 7% and 10% by 2035 compared to the peak, which it announced a few years ago would occur in 2030 but now doesn't specify because, according to Alcaraz, it could arrive even sooner. "It's a very unambitious commitment for the world's largest emitter, but China's commitments have always seemed unambitious and then they far exceed them," says the expert. In contrast, the United States, the second largest emitter, pledged to halve its emissions by 2030 under Joe Biden's administration, but Trump not only reneged on that promise, but also withdrew the country from the Paris Agreement and went all in. to backtrack with his infamous "drill, baby, drill" (pierce, girl, pierce).

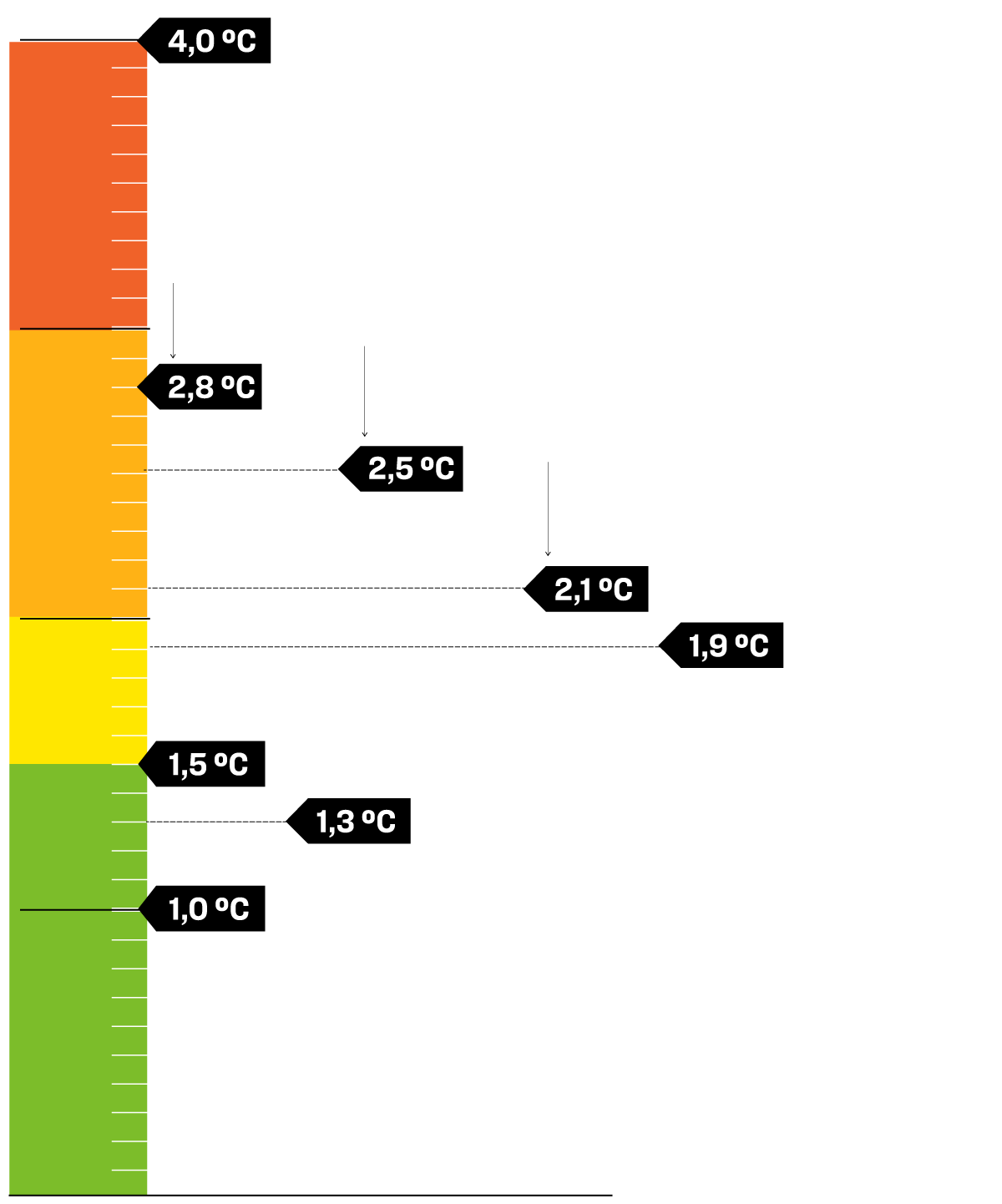

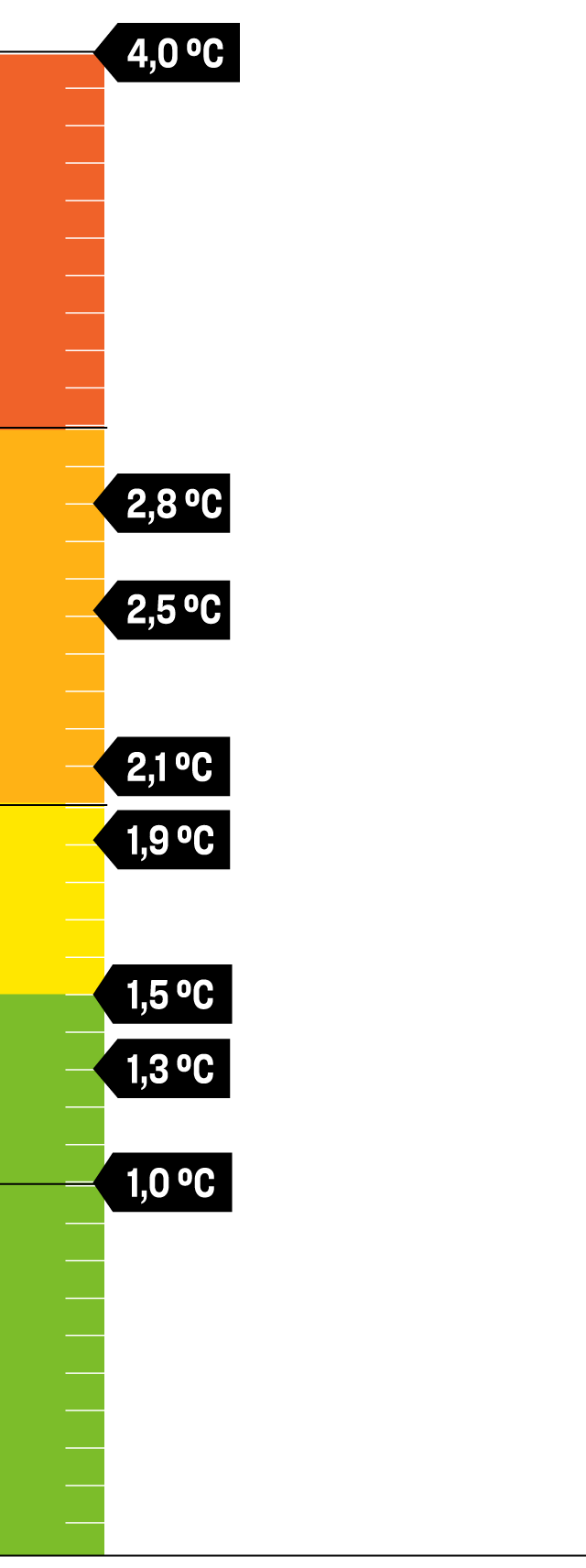

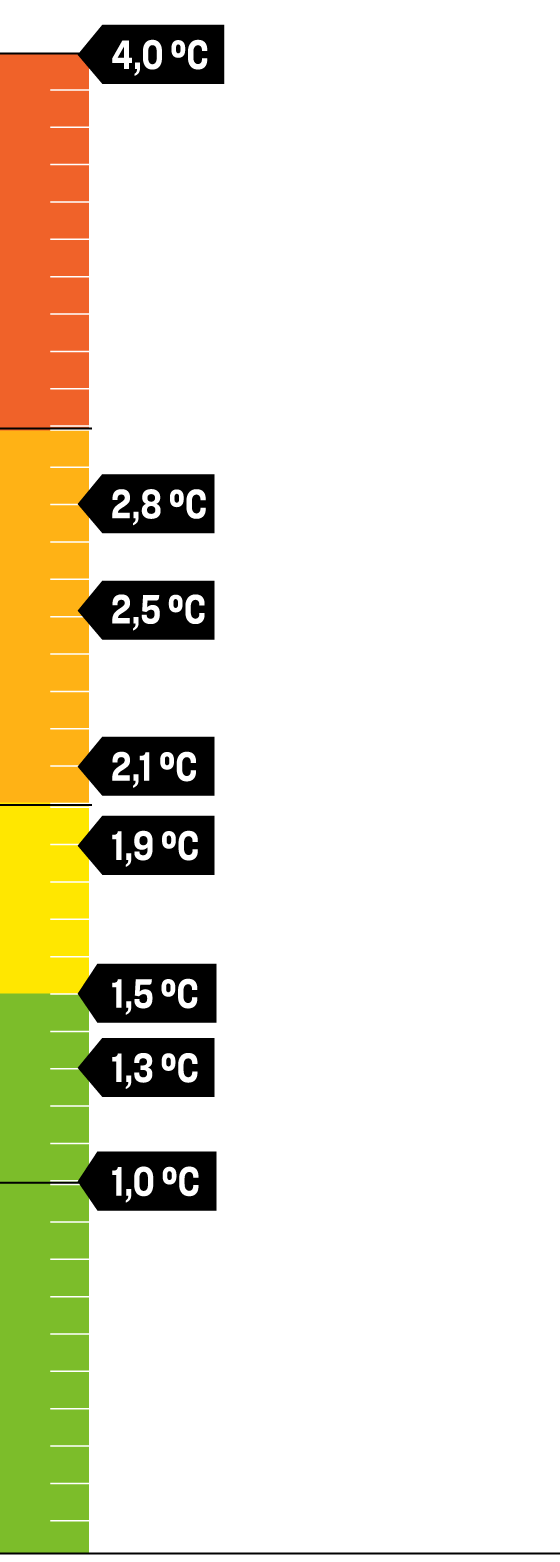

The temperature

But although it may seem ineffective, the Paris Agreement has indeed been useful. Before the agreement was signed, the world was heading towards 4°C of global warming by the end of the century, and now, with the political commitments already presented at COP30, We are heading towards 2.5ºC if the targets are met and towards 2.8ºC if current policies are maintained, according to the latest UN reportIt's still insufficient, but certainly an improvement. When that pact was signed, the global temperature was already around 1°C above pre-industrial levels, but we are now 1.3°C above. This change alone has added another eleven days of extreme heat per year (this year, 2025, compared to 2015), according to a Climate Central study. Extreme heat waves are now more likely than in 2015, which is very worrying, since extreme heat kills around 500,000 people worldwide each year, making it the deadliest weather event.

The 1.5°C red line is getting closer, but scientists say the situation can still be turned around. A study published this Thursday by Climate Analytics says it's possible the global temperature could rise by up to 1.7°C and then begin its downward trend again. For this to happen, electrification would need to reach two-thirds of energy demand by 2050, thanks to the decreasing cost of renewables. This electricity, combined with hydrogen, biomass, and synthetic fuels, would need to displace fossil fuels from the energy system by 2°C. For wealthy countries, this would need to happen even sooner, by 2050.

"The last five years have cost us precious time in the critical decade for climate action. However, they have also seen a revolution in renewable energy and batteries, which have broken records worldwide. Taking advantage of these tailwinds can help us make up for lost time. The window to minimize excess energy is now open. The choice is ours," said Neil Grant, one of the study's researchers. In these last five years that Grant mentions, the incentives for unchecked economic growth following the pandemic have, combined with the rise of far-right climate change denial in many parts of the world, torpedoed the optimism with which the decade of the Paris Agreement began.

Renewables

And although renewable energy has doubled in the last ten years and is on track to triple soon, the reality is that 80% of the energy consumed worldwide today still comes from oil (30%), coal (28%), and gas (23%), according to the International Energy Agency. This is despite the fact that renewable energies, especially solar and wind, have seen the greatest cost reductions in the last decade and are currently the most competitive. Renewables are growing at a rate of 6% annually, while fossil fuels are growing at 1.5% annually. But they shouldn't be increasing; they should be drastically reduced to zero. "The problem is the constant growth in energy consumption, which has meant that all the renewable energy generated is being added to the total instead of replacing fossil fuels," Alcaraz points out. Until this global energy growth is halted, with measures such as greater energy efficiency and a circular economy, it will not be possible to drastically reduce fossil fuel consumption as science demands.

In fact, in these ten years many countries have opened new oil and gas fields and increased the production of these fuels, when what is needed is to stop drilling. The United States is the country that has invested most heavily in oil and especially in gas (and the fracking) in the last In recent years, the US has become the world's leading producer and exporter, thanks in large part to Russia's international isolation due to the war in Ukraine. However, the CIDOB analyst asserts that the United States "is still committed to renewables" and that the wildfire plan approved by Joe Biden is still having "a positive impact." "There's anti-energy transition rhetoric from Trump, but in practice, investments aren't yet heading in that direction, although there is a return to fossil fuels," says Martínez. But Canada, Norway, and Australia have also increased their fossil fuel production instead of reducing it, as have China, Iran, Iraq, and Brazil, which is precisely trying to position itself as a leader in the fight against climate change, taking advantage of being the host country of the host country.

The reef is clearly a symbol of the enormous power of the fossil fuel industry, which is evident even at these UN climate summits and others, such as the one that attempted to approve a treaty to reduce plastic production and failed, or the one that sought to restrict emissions from shipping and also failed. These are all recent failures that signal a shift in the momentum generated by the Paris Agreement in 2015.

More than 225 climate NGOs have formally requested that fossil fuel companies be excluded from UN climate negotiations, but so far they have not been successful. At this year's Amazon summit, hundreds of gas and oil lobbyists will again participate, either as representatives of a country or even as observers. "Until the WHO banned tobacco companies from government negotiations, no progress was made on this issue," recalls Anna Pérez, a researcher at the Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations (IDDRI). Pérez points out that, moreover, "the company that won the bid to manage communications for COP30 is Edelman, the same communications firm that works for Shell in Brazil."

The main objective of this COP30 in Brazil is to finally push for the implementation of the Paris Agreement, after a decade of negotiating the rules and the fine print of that pact. "This implementation must now take place at the national level, but the UN wants to see what more it can do" to facilitate and monitor it, explains Pérez. It already has mechanisms in place, such as the transparency mechanism created by the Paris Agreement to monitor compliance with the national plans (or NDCs) submitted to the UN. The Paris Agreement does not set binding figures and leaves it to each country to submit the commitments it deems appropriate, "but these commitments are indeed binding once submitted," Alcaraz states. Furthermore, since that same year, the International Court of Justice (ICJ) In a landmark ruling, the government has made it clear that complying with the Paris Agreement is a legal obligation for governments.Warning to navigators: you may be penalized if you do not comply.