Is influence only achieved by paying money? The Montoro case spreads fear throughout the business world.

Several executives explain in the ARA the fear of companies, especially large ones, of being singled out

MadridSince Spanish Prime Minister Pedro Sánchez explicitly referred to Ignacio Sánchez Galán, chairman of Iberdrola, and Ana Botín, chairwoman of Banco Santander, in an appearance in the Congress of Deputies three years ago, the business world has been scrutinizing his interventions. "If [these two executives] protest, let's go in the right direction," Sánchez stated immediately after announcing the extraordinary taxes on energy companies and banks. Since then, businesses, especially large companies, have lived with the feeling that they could be singled out at any moment. Now, the outbreak of the Montoro case has set off alarm bells once again, says a businessman close to the major Spanish and Catalan employers' associations.

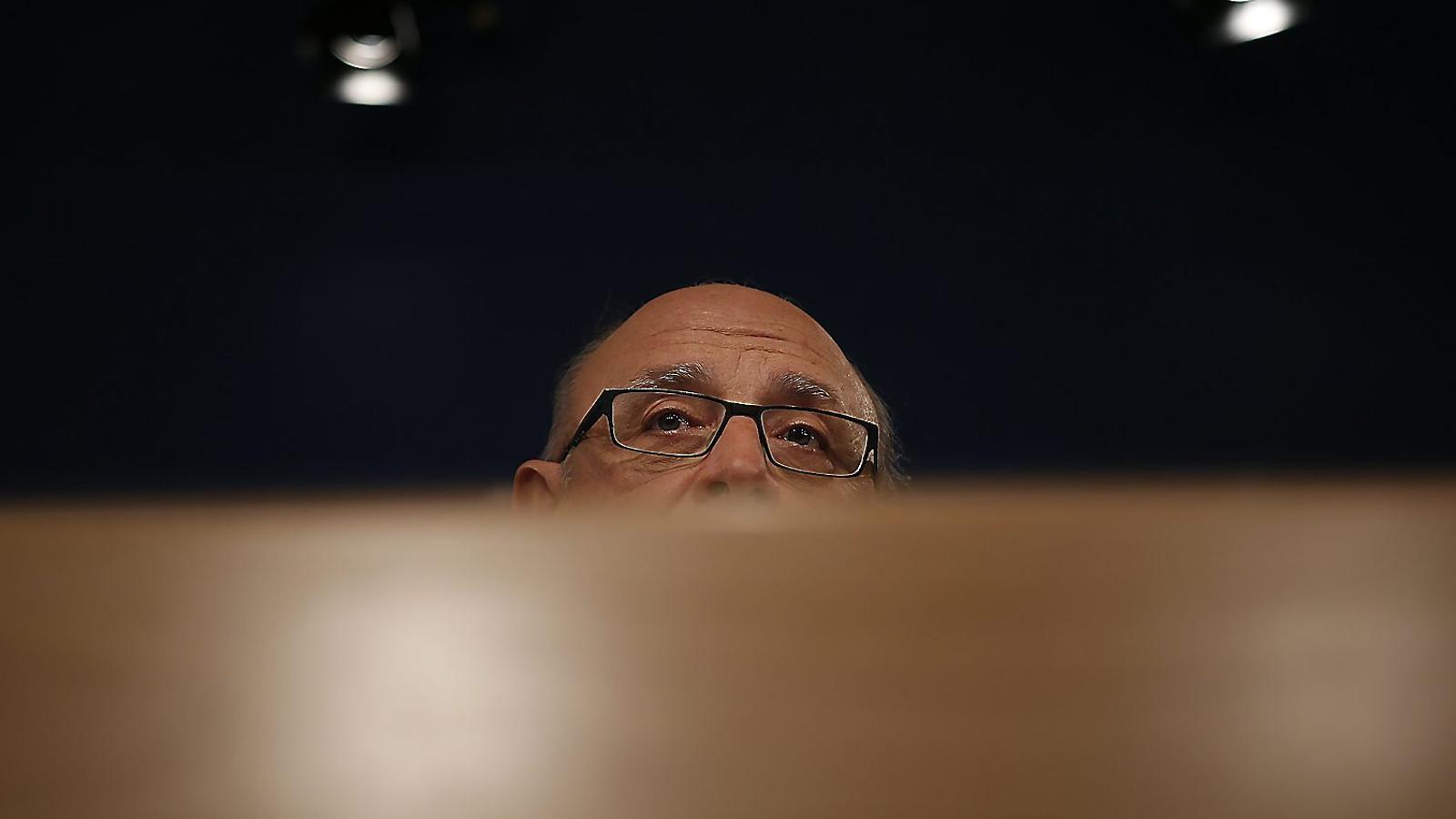

The Tarragona court's investigation into a "network of influence" that allegedly trafficked in laws and that points to the illicit enrichment of the former PP Finance MinisterCristóbal Montoro, and the use of front men, has caused a political earthquake. The case, however, also impacts the business world, specifically several industrial gas companies—14 executives are charged—although it is being seen as a reputational event that hurts the political sphere more than the economic one, according to three business experts consulted by ARA.

"Whoever has done something [illegal], must pay," indicate business sources who condemn the alleged corruption. The same sources state that, in any case, "work continues normally on those issues that concern [the companies], and that's it." In this regard, a source close to Madrid business circles points out that, for the moment, the companies directly targeted by the investigation are part of a very specific sector: industrial gases. In fact, the tax changes at the heart of the investigation affect this activity exclusively. "There has been significant confusion; it has nothing to do with the gas energy sector. We're talking about companies that manufacture gases for production processes in the food or medical industries," sources in the gas sector explained to ARA. In fact, the Third Vice President and Minister for the Ecological Transition, Sara Aagesen, herself a few days ago distanced the gas companies from the judicial investigation: "We're talking about industrial gases; more than the energy sector, we're talking about the industrial sector," she said.

The burden of proof

In any case, cases like this "don't please anyone, they anger them," adds another voice, who believes that this discontent will add to the "political disaffection" that has long been perceived in certain business circles: "The business sector is going a bit on its own. I don't think anyone expects great things from the political parties because the perception is that behind everything there is: behind everything there is: the context."

The businessman from the beginning acknowledges that concerns could increase if there is a shift toward what he considers an "easy" narrative that places "the burden of proof on money, which is what corrupts the politician, and not on the politician who corrupts." When he speaks of this shift in narrative, he looks to left-wing parties. Podemos, in fact, has not hesitated to denounce that "companies buy PP and PSOE politicians as if they were raw materials to develop their businesses; for them, these gestures are necessary if they want to earn much more money in Spain, and they don't spare a single euro: they know that these are the rules of the game," denounced Podemos's organizational secretary, Pablo Fer.

In the business sector, the same voice asserts, they fear that Sánchez will also subscribe to this discursive framework. For now, the Spanish Prime Minister has made a killing with the PP, linking the Montoro case to its way of governing: "Without political autonomy, in favor of the elites and against the citizens," he stated this week in an appearance from Uruguay, during his tour of Latin America, in which he was accompanied by a delegation from BBVA, Sacyr, Indra and Mapfre, along with the Spanish employers' association CEOE, as is usual on this type of trip.

Avoiding the image of marketing

The image the business world wants to avoid is one that denounces that, to get things done, companies always end up paying money. In other words, engaging in marketing. "In cases like this, you always have to look at which companies we're talking about. It's very difficult for small and medium-sized companies to have access to certain levels [of influence]," says another voice, who asserts that it's the "largest Ibex 35 companies" that tend to be implicated in these cases. In the Montoro case, names such as Ferrovial, Solaria, and Abengoa have also appeared, all of them clients of the law firm founded by Montoro, Equipo Económico. In the Santos Cerdán case, also known as the Koldo or Ábalos case, which directly implicates the PSOE, the companies involved are construction companies, including Acciona. "SMEs don't even have the power to reach political interlocutors, while in large companies, it's the deputy director on duty who speaks directly," reflects one of the people consulted.

In the Montoro case, there is also a feeling of expectation regarding the course that the case may take: "Where does the office lobby end and where does prevarication begin?" indicates one person, who recalls that the consulting business is very widespread and that many different economic actors come in... "Everyone asks for advice to participate... consulting firms," he adds.

All in all, beyond the narrative that Sánchez may adopt, it remains to be seen where the so-called regeneration plan that he wants to promote in the next political year will go. And whether it will be an eminently political plan or will also involve companies. "I wouldn't be surprised," indicates one source. ~BK_SLT_NA