Is paracetamol toxic to the fetus? A microplacenta will allow doctors to test it.

Researchers at EMBL Barcelona are working on a device to evaluate drugs and better understand diseases such as preeclampsia.

Thalidomide It has gone down in history as one of the worst cases of devastating side effects caused by a drug. Although there is no official figure for how many people were affected globally, it is estimated that more than 10,000 babies were born with terrible birth defects during the years this drug was marketed.

Synthesized in 1953 by Wilhelm Kunz of the Swiss pharmaceutical company CIBA, while he was searching for new antibiotics, the molecule was given to another laboratory, the German company Grünenthal, which ended up developing it as a non-barbiturate sedative. It was approved and launched on the market in 1957. And it was almost miraculous: the package insert indicated that it was useful for treating irritability, lack of concentration, premature ejaculation, menopausal pain, tuberculosis, and even nausea. It was even recommended for "unusually restless" children. The drug, sold without a prescription, was a huge commercial success and, within a few years, became the third best-selling drug worldwide. However, in the late 1950s, in Germany, where it was most widely used, pediatricians noticed an increase in babies born with malformations or missing limbs, and by the early 1960s they had linked its use during pregnancy to these birth defects. The drug was banned; Spain was one of the last countries to do so, in 1963. But the irreparable damage had been done.

Although the pharmaceutical company Grünenthal He had conducted experiments on monkeys, dogs, and rabbits, administering the substance to them for weeks, and even on pregnant rodents, yet he failed to notice that the animals were less sensitive to it.

More and stricter controls needed to reach the market

The thalidomide disaster, as it was called, led countries to impose very strict controls on medicines before they are put on the market. Since then, pharmacological trials, testing on animals, and ultimately on humans are mandatory for approval before a drug can be marketed. It is a long and exhaustive process, usually lasting more than a decade. However, pregnant women, and also breastfeeding infants, have traditionally been excluded from these medical trials, supposedly for ethical reasons. Administering a substance to a pregnant person to assess its toxicity can potentially harm the fetus. This has meant that, at least until 2025, less than 0.4% of Clinical trials underway in the EU including pregnant women.

If they don't participate in these trials, there is no information about the benefits and risks of a drug during pregnancy and breastfeeding. And yet, many pregnant women must take medication because they have chronic conditions, infections, or pregnancy complications, such as fever or severe pain. In this regard, they will surely remember Trump's controversial first announcement and after the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, The FDA, regarding the possible association between paracetamol use during pregnancy and subsequent diagnoses of autism or ADHD in children

"It's incredible, but today there is no reliable model for evaluating drug safety during pregnancy, which represents an absolute lack of knowledge that leaves both women and children at risk," the researcher believes. Kristina Haase, who has been researching in 2019 European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Barcelona.

This mechanical engineer began her research at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) investigating blood vessels and became interested in the placenta, a highly vascularized temporary organ that supplies nutrients and oxygen to the fetus. Since arriving in Barcelona, Haase has been working on developing a 3D placenta-on-a-chip model as a tool to investigate which molecules are able to cross it and reach the baby.

"Until now, toxicological studies were all basically done on placental cells in the laboratory and in animal models, which, despite being useful and providing some information about the effects of medications, do not represent the complexity of human placental physiology," this researcher points out because, to begin with, she reminds Haase, it's about human pregnancies versus mice; nor is hormone synthesis completely different. Furthermore, "animals also don't suffer the health problems that can appear in human pregnancies, such as preeclampsia," a disease that can be very serious and fatal, and which is exclusively human, adds Marta Cherubini, a researcher at the Copenhagen Institute for BioInnovation and co-developer. An underappreciated organ

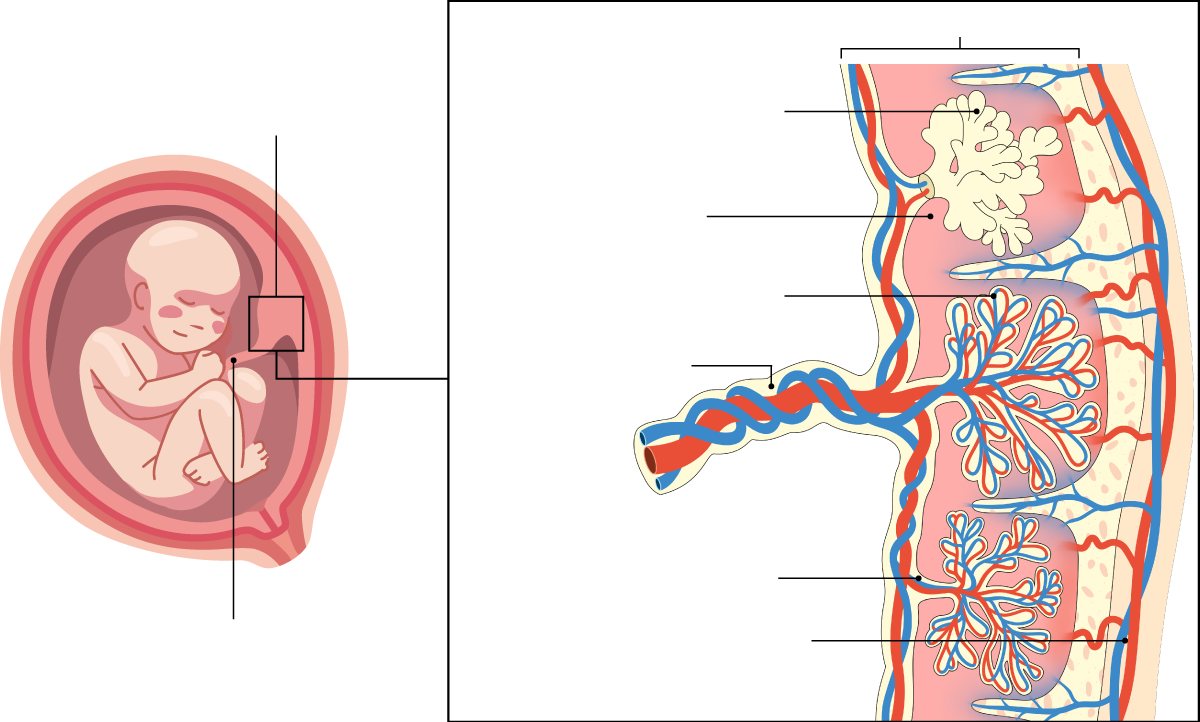

The placenta is undoubtedly a fascinating organ. The body creates it from scratch at the beginning of pregnancy, and it functions at full capacity for nine months, protecting the baby, providing it with nutrients and oxygen, and regulating the exchange of waste and blood between mother and child. It is now known to be a key organ for long-term health, influencing the mother's cardiovascular risk, the baby's future metabolic health, and fetal programming. However, this marvel has a limited lifespan and ceases to function after approximately 40 weeks. Nature's planned obsolescence. Furthermore, it is an organ that belongs to both the mother and the fetus, and its characteristics can vary considerably between women. This has made it difficult to fit into classic biomedical research models, and it has been understudied. Historically, it was also considered little more than waste or refuse that was simply discarded. It's quite a paradox to think about how a woman's body is medically controlled during pregnancy, yet for a long time the very mechanism that sustains gestation—the placenta—has been overlooked.

Haase and Cherubini want to help end this lack of knowledge, yet another example of the gender biases that have surrounded women's health, which has been undervalued by science and medicine. The two researchers have been able to reproduce a simplified placenta on a chip, showing the maternal portion, separated by specialized trophoblast cells that act as an interface between maternal blood and the chorionic villi of the placenta, and the fetal portion, the fetal vasculature. Furthermore, it is perfusible, meaning it allows fluids to pass through.

"We have already tried to pass molecules of different sizes and have been able to reproduce what happens in human physiology," Cherubini proudly points out.

A three million euro boost

Now, the Copenhagen Institute for BioInnovation has just awarded three million euros in funding to this project, aiming to help researchers develop a commercially viable toxicity testing service within three years. "Each individual chip takes a long time to make, and each experiment requires between 40 and 60," says Cherubini, who points out that "it's an enormous and difficult-to-reproduce effort." Since the chip is composed of different types of living cells, it takes at least three days to make. "The biggest limitation is precisely that we have to wait for the cells to grow. We can't accelerate this process," adds Haase. In addition to assessing whether drugs reach the fetus and whether they are toxic, the placenta-on-a-chip will also be used to analyze other substances, such as caffeine. It also opens the door to shedding light on the impact of other fetal exposures on the future health of children and adults. "We started looking at particles from pollution and PFAs, or persistent organic pollutants, present in plastics to study their influence on pregnancy," Haase points out. Another potential application of this device will be to better understand the physiological processes that occur in this organ by observing it. in situThis would shed light on some of the problems related to this organ that can cause pregnancy loss. Currently, two out of every ten confirmed pregnancies still end in miscarriage, especially during the first trimester. Or diseases that can endanger the lives of the mother and baby, such as preeclampsia, which is one of the most common pregnancy conditions. In this regard, the researchers have a project funded by La Marató de TV3 in which they are collaborating with a team of doctors from Vall d'Hebron Hospital to better understand the origin of this disease using samples from pregnant women, with and without the condition, and these 3D placenta chips. Pregnancy is medicalized, but the mechanism that makes it possible has not been sufficiently investigated. With this placenta-on-a-chip, these researchers want to change that.