Incunabula, rare books, bibliophile editions, documents with autograph signatures... fill the Depósito de las Aguas (Water Deposit). Some of the most important collections it houses are: the Alois M. Haas Collection (of theology, religious studies, and philosophy), the Jaume Vicens Vives Institute of History Library, the Oriental Studies Collection, and the Barcelona Chamber of Commerce Collection. There are also three archives of major philosophers: Eugeni Trias, Gianni Vattimo, and Xavier Rubert de Ventós, in addition to the Palau-Ribes Papyrological Collection. Finally, you will find a small permanent exhibition on Pompeu Fabra, the linguist who established the modern Catalan standard, after whom this university is named. There are his works—first editions are particularly noteworthy—and works that discuss him.

Porciolas, deep-sea navigator

The Water Reservoir of the Ciutadella Park in Barcelona

A water bottle, a pencil case, a blue pen and a red one. A pile of closed books and an open notebook. A glass that I imagine contains coffee, but it's covered—it's necessary to do so in case the liquid tips over and spills. This is the arsenal of the girl with Asian features I see sitting at a table, headphones on (and it's deathly silent. Is she listening to music? What music?).

The silence is only occasionally interrupted by lions and other animals from the nearby zoo. And by the tram that runs along Wellington Street. Loud talking is frowned upon here. If you prefer heels rather than flats, you might not want to go near it. And if you laugh or cough easily, this isn't the place for you.

It's Sunday. Yes, this space, which has a long name (Library/CRAI – Learning and Research Resource Center) and belongs to Pompeu Fabra University, is also open on weekends. It's a study room, a reference room, and a repository for unique bibliographic collections.

Mercè Vilalta, one of the library managers, tells me—whispers—a lot of things as we stroll among the books. Before becoming a library, this building had many other uses. Its initial purpose was as a water reservoir. This reservoir, located about 16 meters high, was to irrigate the gardens of Ciutadella Park and supply the park's waterfall. The water was collected from the water table and pumped up to the top of the building by motors.

The water was at the top of the building. Beneath the water there is a huge space that was quickly used. Thus,After its construction, it housed the mining pavilion for the 1888 Universal Exposition (a bridge was built for this occasion connecting the reservoir with Ciutadella Park). Later, it served as a municipal asylum (you can read this name in half-erased letters on the exterior of the building, next to Wellington Street), a fire department warehouse, and the archives of the Palace of Justice. For the Barcelona Olympic Games, it hosted an exhibition on the works carried out in Barcelona for this event. It was in 1992, in fact, that the Water Reservoir became the property of Pompeu Fabra University. It was inaugurated as a university library, after being renovated and refurbished, in 1999.

The architect—then called master builders—of this building was Josep Fontserè (1829–1897), the developer of Ciutadella Park, which had been a military citadel. Fontserè designed the Depot in 1874, around the same time he also designed the Born Market, together with Josep Maria Cornet i Mas (a relative of mine; my surname is Cornet on my mother's side). In the Born Market, he used the then-modern technique of cast iron pillars, which he rejected for this depot, as it was risky due to the height and weight of the water.

"Fontsereno modeled the structure of the Piscina Mirabilis in Bacoli (near Naples), from the time of the Emperor Augustus," explains La Mercè. "Unlike the Roman building, he decided to place the tank on top of the building, which allowed for windows to be opened inside," he tells me. "It's still to be renovated, and there's no date yet for when it will be done. This area is roughly a third of the tank."

It's said that Antoni Gaudí (and Cornet—also a distant relative of mine) did the structural calculations for the building when he was an architecture student. He did it so well that he passed a class without having to return to class.

We're now in a loft, which has plenty of nooks with study tables, where practically no one can see you. "All the library's elements—the shelves, the stairs...—just touch the walls. None of them touch the original structure. From one day to the next, it could be just like the warehouse was in its early days.

The architects who carried out the renovation, Lluís Clotet and Ignasi Paricio, weren't at all invasive. "So they decided to empty it. Now, photovoltaic panels are being installed on the building's roof," Mercè tells me as I look at several encyclopedias, an endangered species (in the world outside libraries).

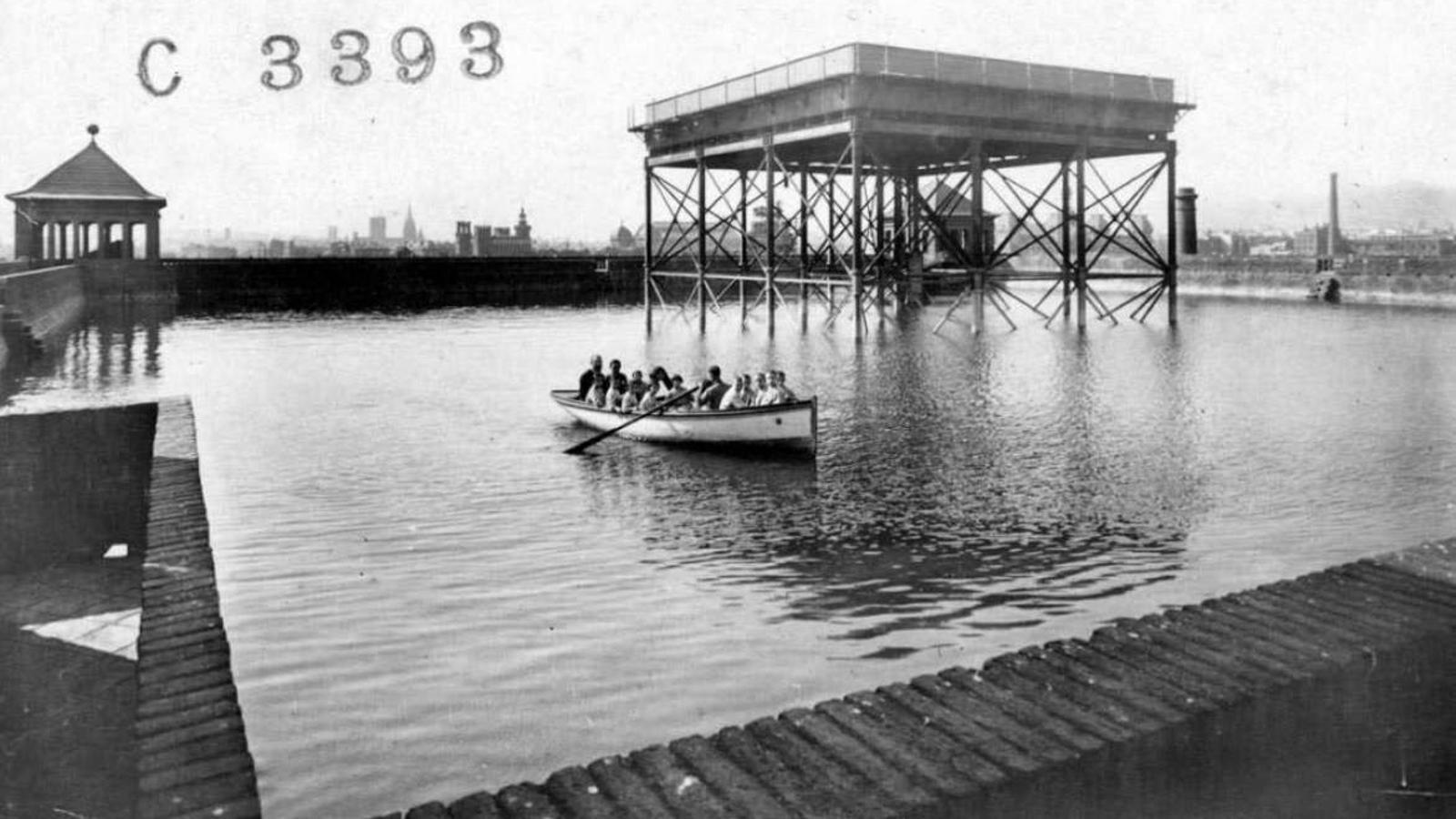

In the attic, I see some old photos on display. The one that most catches my eye is a black and white one showing about twenty people in a rowboat. They're sailing across the water reservoir. Since the water was for irrigation, not drinking, there was no problem. It's said that on Sundays, Josep Maria de Porcioles, the longest-serving mayor of Barcelona during the Franco regime, would take these boat rides.