Irregular departures from Ukraine skyrocket due to the escape of men of military age

The tightening of martial law is causing many Ukrainians to leave the country even though the army is facing a manpower crisis.

BarcelonaDuring World War II, the press in the countries involved largely refrained from writing about men fleeing to avoid fighting on the battlefield. Talking about it was considered to be against the nation's interests and favor the enemy's narrative, which used propaganda to attack troop morale. Eighty years later, discussing desertions remains taboo for armies at war. In Ukraine and Russia, both at the center of trench warfare provoked by Vladimir Putin's invasion, cases of men clandestinely fleeing their countries because they did not want to fight abound. Some were already at the front; others—the majority—are fleeing preemptively to avoid being drafted now that, after three years of particularly deadly combat, numbers are dwindling.

While reliable figures are difficult to come by in any war—governments hide or manipulate them to avoid giving the enemy any clues—at the beginning of the year, Ukraine’s General Justice Service reported that more than 100,000 soldiers had been drafted in February 2022. The pace had accelerated especially in the final months of 2024. As a spokesperson for Ukraine’s State Bureau of Investigation recently told the Associated Press, prosecutors and the military prefer not to press charges against captured deserters if the soldiers agree to return. This data refers to soldiers who had already been called up. Kiev has not released information about evasions by men of military age who had not yet been mobilized.

Ukraine has long has serious staffing problems on the frontThe soldiers who have survived three years of war are exhausted and lacking in prominence, as the rate of voluntary enlistment is far from that of the first months of the conflict. Faced with this shortage of personnel, the Ukrainian government tightened martial law in April 2024, lowering the minimum recruitment age from 27 to 25. intensifying mobilization campaigns throughout the country and tightening border controls to prevent escapes. Since the beginning of the invasion, martial law already decreed that men of military age (18 to 60) were prohibited from leaving Ukraine, with a few exceptions: those who had a disability or illness, had three or more children, or were caring for a dependent person. With the tightening of the law, some of these exceptions disappeared.

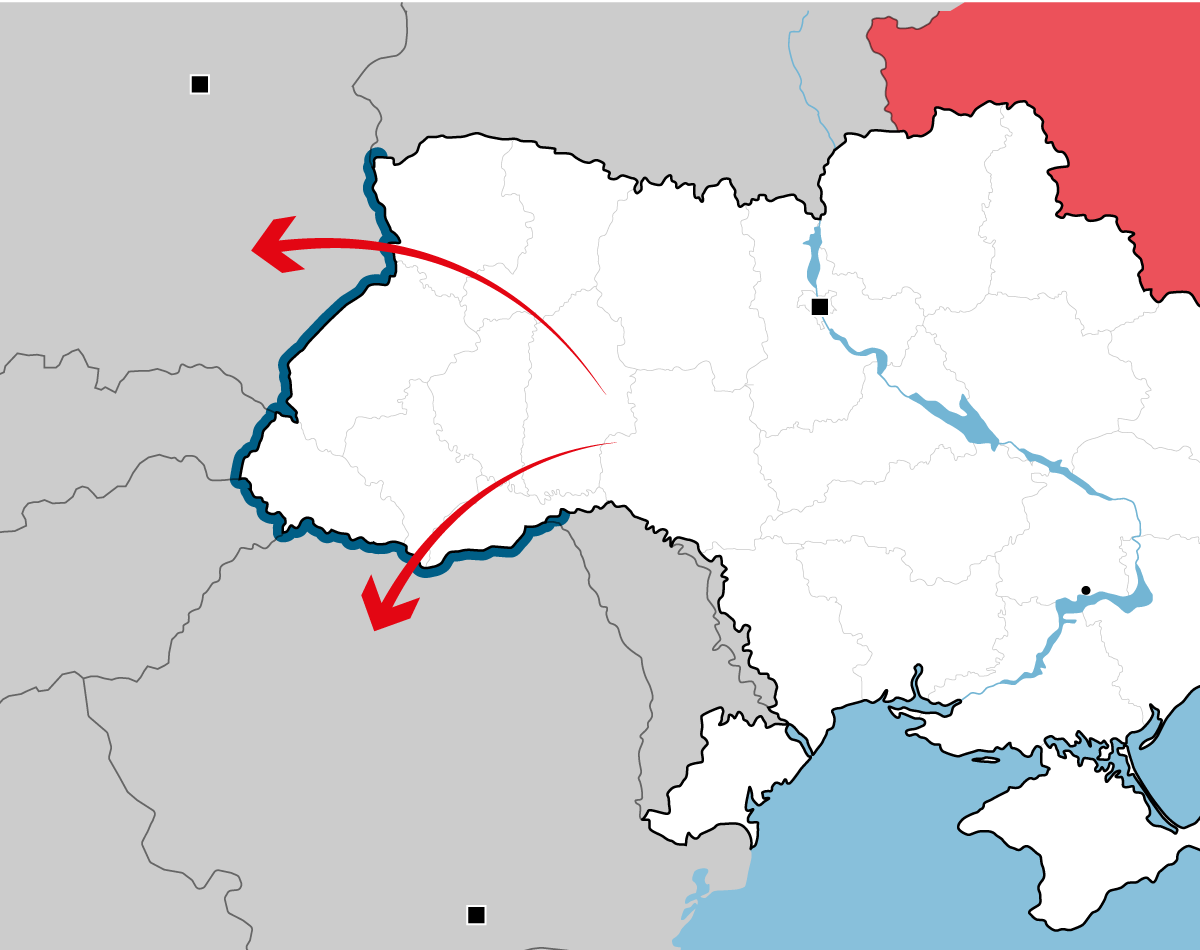

It is in this context that the number of Ukrainians of military age fleeing the country has increased. Data from Frontex, the European agency that controls EU borders, to which ARA has had access, show that during 2024, up to 14,490 Ukrainians managed to leave the country irregularly for the European Union, more than triple the number in 2023, when there were four. In May of that year, just after martial law was tightened, the number of attempts intercepted by EU border authorities doubled compared to April. And the moment when this figure was highest was in July 2024, when 2,035 people with Ukrainian nationality crossed the border irregularly. A figure five times higher than just a year earlier, in July 2023.

In the first months of this year, the number of departures has decreased (a trend justified by the winter cold), but it is considerably higher than last year. It should be emphasized that these data only show people who have been intercepted by authorities in European Union countries. That is, these people had already managed to cross the Ukrainian border.

The irregular entries into the European Union detected must be men of military age (from 18 to 60 years old), because they are the only ones prohibited from leaving the country since Ukraine declared martial law at the beginning of the invasion. This was confirmed to ARA by Frontex spokesperson Chris Borowski, who asserts that, "in all likelihood," these departures are men seeking to "avoid recruitment." They could also be soldiers abandoning their front-line duties.

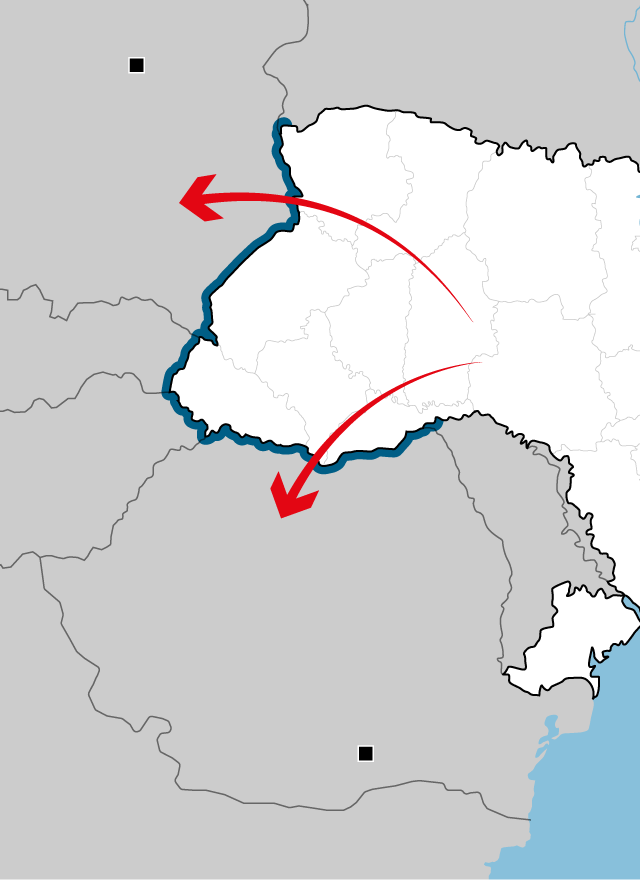

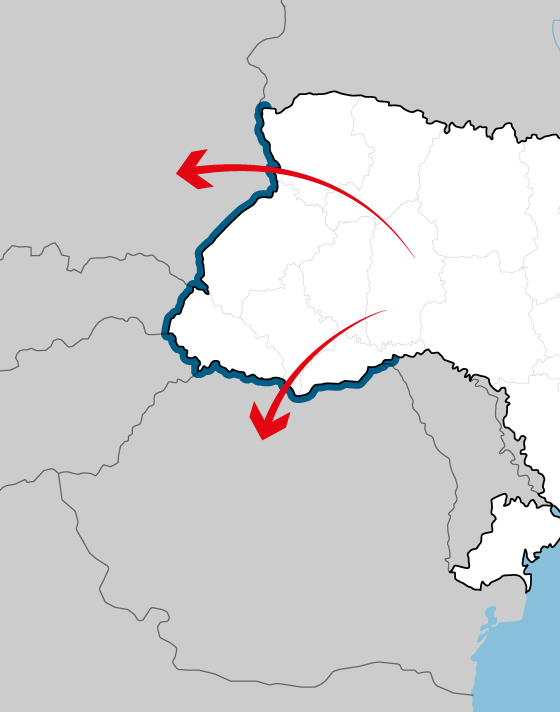

The Romanian NGO HIAS agrees, confirming that they have seen an increase in Ukrainian men and young men crossing the border since May 2024. Typically, Yiftach Millo, the organization's spokesperson, explains to ARA, they come from the Odessa region and request accommodation in the Romanian city of Galat. Millo attributes this "recent phenomenon" to young people avoiding military service, but insists that the humanitarian organization does not distinguish between those who have entered the country legally and those who have entered illegally. Romania, along with Poland, are the main countries of entry into EU territory. The spokesperson for the Polish organization Ukrainski Dom also confirms this trend to ARA, saying that she has noticed an increase in Ukrainian youth between the ages of 15 and 17 arriving in Poland before martial law prohibits them from leaving.

The fact that Romania and Poland are the main entry points doesn't mean that Ukrainian citizens necessarily stay. From there, they often travel to other countries in the European Union. Barcelona, in fact, is a European city that has welcomed a considerable number of refugees from Ukraine. Xavier Cubells Gallès, director of Immigration and Refugee Services at Barcelona City Council, also explains to ARA that the profile of Ukrainians arriving in the Catalan capital has changed. "At the beginning of the war, it was mostly families arriving by car, mainly women and children. Lately, we have seen the arrival of men of military age, some of them with complex psychological profiles.".

A deadly journey through Romania

Military-aged men seeking to cross the border often pay criminal gangs—in cash or even cryptocurrency—to obtain forged documents or to guide them through uncontrolled border crossings. Some of the most common routes cross the Tisza River, which separates Ukraine from Romania and Hungary, or head deep into the Carpathian forests to reach Slovakia and Poland. These are dangerous, deadly journeys that cost between €5,000 and €13,000 per person.

One of the Ukrainians who escaped conscription is 32 years old and originally from Berdyansk, in the Zaporizhia region. He prefers not to speak directly to the ARA for fear of "getting into trouble," and tells his story through a friend. Last spring, after some friends successfully escaped, he contacted "a guide." He was clear that he didn't want to go to the front. He says that for 12,000 euros, the trafficker organized a trek for him and four other men that would take them through the forests to Romania. The weather was expected to be good, and the guide told them they would only need light jackets, sneakers, a couple of bottles of water, and some energy bars. But halfway through the route, a clash between another group of fugitives and Ukrainian patrols forced them to change their route. Then their luck turned sour. It started to rain cats and dogs, and the temperature plummeted to minus twelve. Without shelter, they spent the night sheltered under the trees in the forest. One never woke up. Death from hypothermia. The rest had to continue.

On the fifth day of the journey, they were rescued by a Romanian border guard helicopter, which transported them to EU territory. The protagonist ended up hospitalized in a Romanian medical center. Although they managed to save his frostbitten limbs, he still suffers intense pain today. After obtaining refugee status, he traveled to Spain in the fall of last year, although he later moved to the Netherlands.

Cases like this are repeated. Just a week ago, border guards rescued another man in Zakarpattia after two days of wandering in the mountains, suffering from severe frostbite. This Saturday, Ukrainian authorities decided to strengthen border surveillance between Ukraine and Romania and Hungary. Drones will soon be used to detect men attempting to escape.

"And what about me? Don't I have a family?"

Every desertion or escape of a potential soldier can be celebrated as a small victory by the enemy. Therefore, sources within the Ukrainian armed forces consulted by ARA denounce that Russian propaganda seeks to influence this reality. Moscow's disinformation attempts to infiltrate every corner of Ukraine and exploit the weaknesses of the weary population. Social media is full of videos supposedly showing Kiev authorities beating men in the street to force them to enlist. According to the Ukrainian Center for Combating Disinformation, 70% of the videos are fake, the product of psychological operations coordinated by Moscow. ARA has verified that desertions and evasions are also common in Russia, where accessing official information is simply impossible: the opacity of Putin's regime, which adapts reality to its interests if necessary, is total.

Social stigma has historically accompanied those who flee from combat. It happened in the Roman Empire—where they were severely punished by their comrades—and it continues now. That's why the interpretation made by Ukrainian soldiers who have spent three years on the battlefield, defending the country from the Russian invasion, is interesting. "We understand those who have spent years on the front lines when they can't take it anymore. We tell them: 'Go, rest, and come back if you can,'" a 28-year-old soldier tells ARA from a position on the Donbas front. The soldier warns: "But those who escape by river or through the forest [before being drafted] I can't call them men." "They say they do it for their family. What about me? Don't I have a family? I want to go home too."

This last group, that is, those who choose to preemptively flee from conscription, cite hundreds of reasons. The most common: they say they don't want to die for a corrupt state, they demand that deputies and their children be mobilized first, or they claim to be in poor health. Only a few honestly admit that they have a deep fear of dying.