"For children, fucking can be like giving a hug."

Rethinking sexuality makes it easier for families to talk to their children.

BarcelonaWhat do children know about sexuality? And how do they experience it? This is the starting point of SexAFIN, the action-research project on affective-sexual and reproductive education in educational communities. The research is promoted by the AFIN Research Group of the Anthropology Department at the UAB, which is dedicated to research on families, reproduction, childhood, and sexuality. SexAFIN was established in 2017 in two schools in Gelida with children in 2nd, 4th, and 6th grades. Since 2019, it has expanded to include children and young people from 13th to 4th grades of Compulsory Secondary Education from around forty public and private schools throughout Rio de Janeiro (Brazil) and KwaZulu-Natal (South Africa).

A taboo subject

The proposal arose from the doctoral research of Bruna Álvarez, a professor in the Department of Anthropology and a researcher with the AFIN Research Group, focusing on the social construction of motherhood in heterosexual couples. This, coupled with the fact that other members of the group worked in adoption and assisted reproduction, led them to notice the differences in how adults explained their origins to their children: "Parents of children born from heterosexual relationships don't explain their origins to them; sexuality remains a taboo subject, and there was no research on it." At the same time, Estel Malgosa, co-founder of the project, completed a master's thesis on adolescent motherhood in Nicaragua and observed how girls and young women had their own way of constructing sexuality.

SexAFIN is conceived as action research, which requires the anthropologists of the AFIN Research Group and Center to create spaces for dialogue with the entire educational community to discuss the various dimensions of sexuality. In practice, this means not only asking questions of children, but also seeking the opinions of teachers and families about sexuality, a topic that remains taboo. "This is one of the differences. We always assume that adults know a lot about sexuality, but it's never presented as a dialogue, nor are children invited to participate in the research by asking questions," explains Estel Malgosa, PhD in Anthropology.

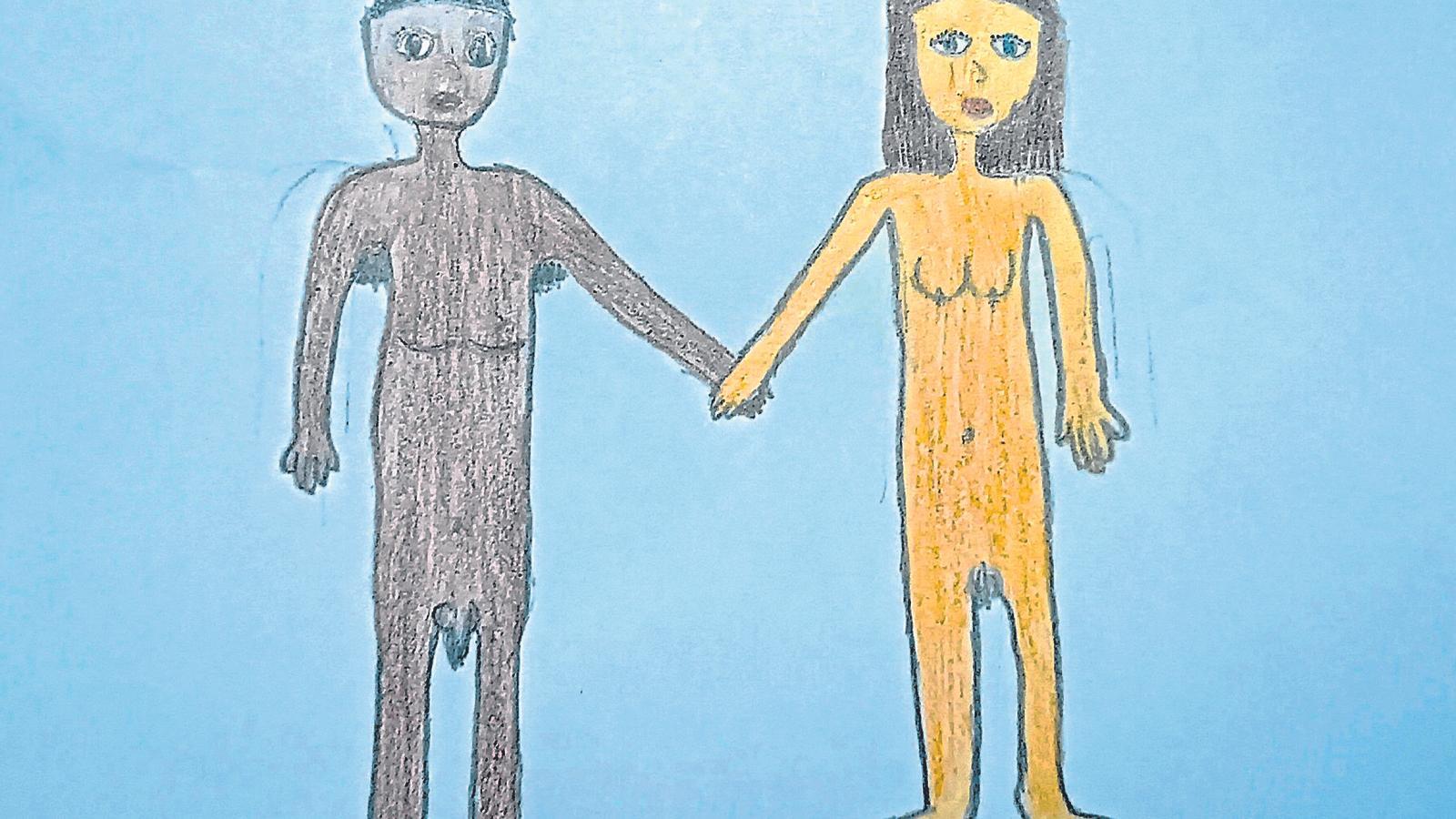

In February, the UAB Exhibition Hall hosted the exhibition Sexualities and Childhoods: Building Knowledge , which presented the results of the SexAFIN project with thirty drawings created by children aged 7 to 11 from various public primary schools in the province of Barcelona, providing insights into how they think, interpret, and signify. The documentary (Re)thinking Sexual Education , based on the SexAFIN study, was also screened. It was broadcast on Sense Ficció-TV3 and is available for viewing on the 3Cat platform.

Different perceptions of sexuality

So far, the research has yielded common results. "It's logical; the people who participated are part of a similar social and cultural framework," Malgosa points out. Children are evidently aware of sexuality in their daily lives and construct their own meaning, even if it's not the same as that of adults. Álvarez recommends that adults not view children's sexuality through an adult lens, because that's when they panic. Young children have experiences through the body; they talk primarily about body and pleasures, and they frame this within the context of sexuality, in accordance with the World Health Organization (WHO) definition. On the contrary, when adults are asked about sexuality, they focus on heterosexual intercourse because the sociocultural context views sexuality in this way, in a limiting way. On the other hand, when children are given space to construct their worlds linked to sexuality, it expands. "Children teach us to understand sexuality in a more holistic way, not just focused on sexual practices. For them, many things are sexual," says Álvarez.

The WHO defines sexuality as a central aspect of human beings throughout their lives and encompasses sex, gender identity and roles, sexual orientation, eroticism, pleasure, intimacy, and reproduction.

Anthropological research

The most distinctive aspect of anthropological research is that it considers all responses valid. "We ask questions and are open to any answers that arise. We analyze children as if they were their own cultural group, capable of constructing their own meanings of sexuality, even though they often don't coincide with adults' findings. For example, for children, fucking can be like giving a hug," says anthropologist Álvarez. What they propose is to stop perceiving sexuality as something adult and closely linked to sexual practices, and to stop understanding children as innocent, asexual beings who must be protected from sexual knowledge.

Once they have the research results, they provide feedback to the school and their families, and from there, the AFIN Group offers them contextualized training. Based on the findings, they provide customized training to address the questions each school raises: "It's personalized attention; it can be training for teachers, workshops for students, or families." Álvarez concludes that it's important for children to know that when talking about sexuality, everything can be discussed because "otherwise, many taboos are created by both the children and the teachers and their families."

How to talk about sexuality with children? Talking about it often makes adults more uncomfortable than children. Marta Pujol, an affective-sexual educator and author of Cambios. Un viaje por la pubertad (Changes. A Journey Through Puberty, 2024), suggests doing so with these recommendations in mind:

1. Start by examining yourself. Identify your beliefs and ideas about sex education and sexuality to avoid biased perceptions and be fully aware of what you're teaching and communicating.

2. Be open to any questions. It's important not to be shocked or repress questions or comments. Families should also be a guide and support their children's sexuality as they do in other areas of life.

3. Don't worry if you don't know everything. You don't need to know everything. If someone asks you something you don't know, just say it naturally, knowing you'll find out what you're doing, and give them the answer as soon as possible. Depending on their age, you can even look it up together. When answers aren't given, it becomes taboo.

4. Dialogue. Communication is key. It's not about interrogation; it's about talking, about two-way communication. Consider your child's personality and respect their temperament.

5. Talk to them from a young age. Attitudes based on gender stereotypes, such as the type of toy or the color of clothing, already imply affective-sexual education. Remember that sexuality is much more than sexual relations. When children are curious about their own bodies, it's not from an erotic perspective.

6. Don't overwhelm them. If you talk constantly, they'll stop listening.

7. Sexuality is much more than sexual practices. Sexuality also relates to emotional issues, body perception, self-knowledge, standards, and aesthetic pressure.