50 years since 'Born to Run,' the album that made Bruce Springsteen Bruce Springsteen

A book recalls the complicated process of recording the album, with the musician's career hanging in the balance.

BarcelonaEvery August 25th, the day the album was released Born to run, Bruce Springsteen He gets in the car for a drive while listening from beginning to end to the album that, he says, "changed his life" for both him and his band. "The car always takes me to Long Branch [a small town in New Jersey], to West End Court, where the house where I wrote the songs is. And I make sure to always arrive before Jungleland. I park there, sit on the sidewalk, and let the whole song play."

This Monday will mark 50 years since the release of the album he recorded at his most difficult professional moment, with his record deal hanging by a thread and his studio perfectionism reaching ill-defined levels. his voice as an artist and that catapulted his career. It's not his first great album, but it is the album that gave birth to the legend of Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band. Tonight in Jungleland, a book about the creation of Born to run written by Peter Ames Carlin, who in 2012 already published the biography of the musician, Bruce. It is to Carlin, in fact, that Springsteen confesses the small homage he makes on the album every August 25th. The book is absorbing to read and portrays in detail how fragile Springsteen's professional situation was in 1974, when, after signing with Columbia, backed by comparisons to Bob Dylan, he had barely sold 40,000 copies of his first two albums. In addition, his supporter at Columbia, Clive Davis, was no longer managing the company and his successor saw nothing special in that shaggy guitarist from New Jersey.

"It was obvious that if the next album didn't succeed it would be the end of his career," summarized guitarist Steve Van Zandt in Wings for wheels, the 2005 documentary about the recording of Born to run. But Columbia couldn't even bring itself to commission a new album, and first asked for a radio-friendly single. And it was an understandable request: the first two albums were magnificent and full of great songs, but they didn't connect with the audience like Springsteen and his band's live performances did, with their exuberant, catchy energy.

Under maximum pressure, the musician embarked on the most difficult recording of his career: he and the band spent six months in the studio shaping the song. Born to run, adding layers and layers in search of a kind of Phil Spector-esque wall of sound. Most of the ideas would be left out of the final mix (string arrangements, a heart of female voices, sound effects), but the result was extraordinary, a sonic explosion that did justice to that song about the urgent need to escape from one's own life, no matter where. Springsteen had worked on the lyrics for months, and in a way, they outlined the major themes of his work. "The questions I would try to answer in my songs for the rest of my life first took shape in Born to run –he reflected on Wings for wheels–. What do you do when your dreams come true? And when they don't?

Rebuilding a band in a hurry

The first Columbia executive who heard the song was not impressed, probably because he listened to it while on three simultaneous phone calls. Understandably pissed off, Mike Appel, Springsteen's manager and producer, leaked the song. Born to run to a handful of radio DJs who played the song on their shows. Listeners' enthusiasm for this stunning song led Columbia to commission Springsteen to record his third album, but now he had another problem: one of the key members of his band, pianist David Sancious, was leaving the E Street Band to pursue a solo career, and with him was his friend, the bat Boom Postman. Sancious was a significant loss, as Springsteen had designed the band's sound and some of the songs to allow room for improvisation and the pianist's genius. They hurriedly placed an ad on The Village Voice and found replacements – Roy Bittan and Max Weinberg – who gave the band a new sound: from the hyperactivity and improvised outburst of the first albums to a more sober and fluid style but, overall, more powerful and defined. The sound of Born to run.

To capture the rest of the risk, Jon Landau, a journalist from the magazine, was also brought in as co-producer. Rolling Stone who wrote: "I have seen the future of rock'n'roll and his name is Bruce Springsteen", in an enthusiastic review of a concert by the New Jersey native. More intellectual than Appel, he won Springsteen's confidence and helped him get a better studio and polish the sound and arrangements, especially with Thunder Road, which he restructured from top to bottom. After Born to run, Landau ended up replacing Appel as manager and producer, but during the recording the creative tension between the two producers was positive for the album. And contrary to what it might seem, it was Appel who prevented the magnificent Meeting across the river, a jazz-inspired song with storytelling lyrics black, fell from the record in favor of the more conventional ones Linda let me be the one and Lonely night at the park. These are, by the way, two of the few songs from the sessions Born to run that were left in the drawer of the study, although Linda let me be the one would end up seeing the light in 1998 in the compilation box set Tracks, and Sony just released Lonely night at the park to commemorate the birthday of Born to run.

Van Zandt, providential

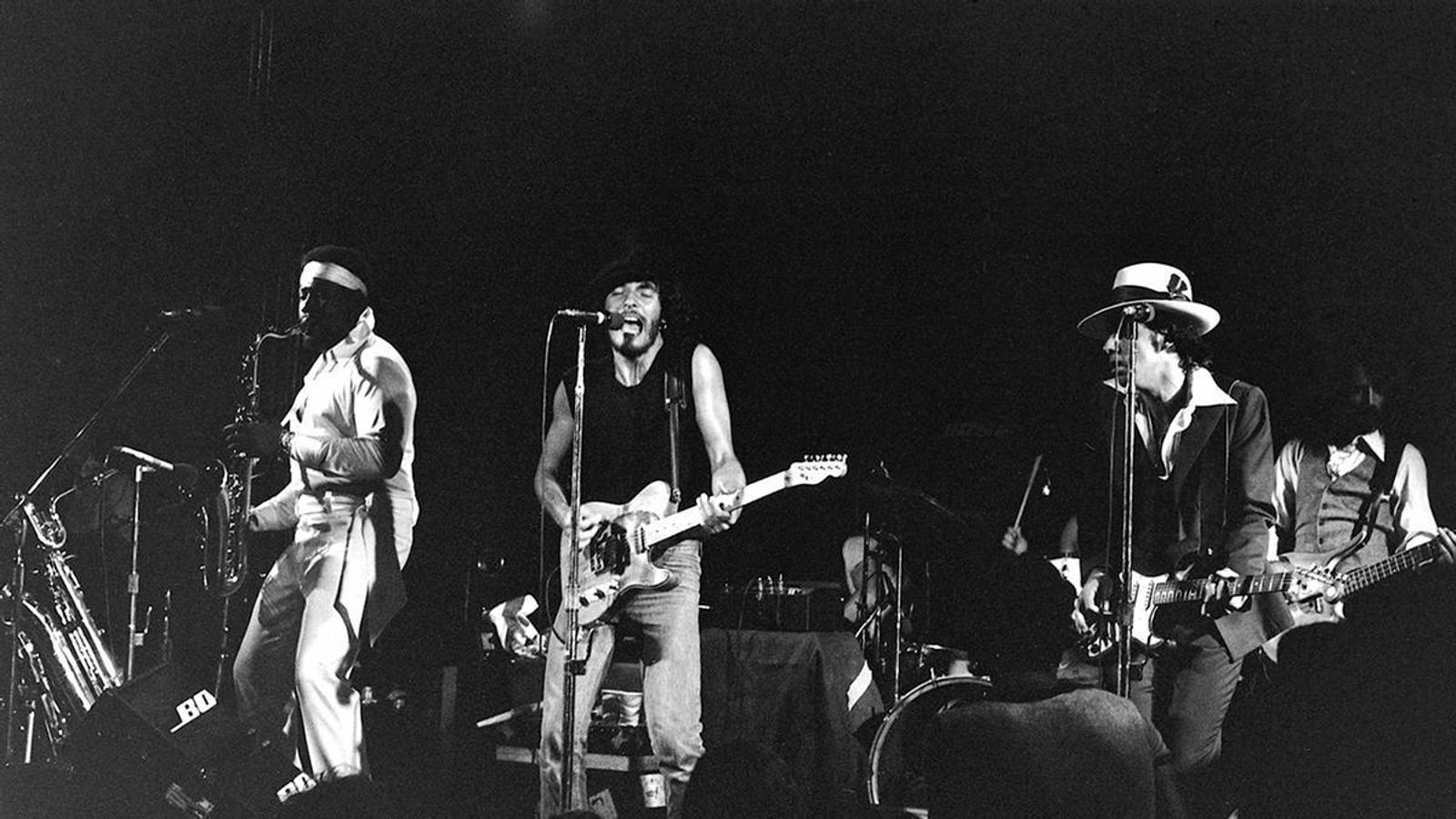

During the recording of Born to run, the pot of ambition and insecurities that was the 25-year-old Bruce Springsteen skyrocketed his levels of demand and obsession with recording the ultimate rock album. One of his victims was Clarence Clemons, whom he made play the saxophone solo for days on end. Jungleland, indicating note by note how he wanted it. But one of the most famous anecdotes of the recording of the album is the providential appearance of Steven Van Zandt, who doesn't play a single note in Born to run –not yet part of the band–, but who visited the studio the day a wind section got stuck with Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out because they were used to working with sheet music. Van Zandt, always intuitive, took the right path and sang the parts they were supposed to play, with immediate success. That was the moment Appel and Springsteen agreed to officially bring the guitarist into the E Street Band.

Born to run recording is finished in extremis In a final three-day marathon with barely any rest because the group had to go on tour, but there was still the final twist. When Springsteen received a test copy with the final mastering and listened to it, he was suddenly devoured by all his doubts and insecurities. Perhaps that album, after all, was garbage, and he was a talentless show-off. He threw the album into the hotel pool where he was staying and said he had to start over, that it was worthless. Ultimately, Landau and Appel brought him back to his senses, but, in retrospect, in that inconsequential outburst, one could already detect the self-esteem and anxiety problems stemming from his poor relationship with his father, which in the future would end up driving Springsteen to therapy for more than twenty years to appease his inner demons.

From cover to cover

Preceded by legendary gigs at New York's Bottom Line club, Born to run It was received as an instant rock classic, a masterpiece from head to toe, from the lyrics to the music and the iconic cover with Springsteen leaning against Clemons. Incidentally, the fact that only the two of them appeared on the cover was a decision by the singer, partly to underline the idea of friendship that ran through the songs, but also because he wanted to send a message of racial integration that, deep down, was already present in the mix of rock and soul that was his music.

He had less control over the media uproar that formed around him, when the two most influential magazines in the United States, Time and Newsweek, dedicated the cover to him, and precisely the same week. The first one dedicated a complimentary article and considered him "the new rock sensation", while the second one had a more skeptical view and analyzed the phenomenon of Born to run As a great marketing campaign, perhaps the worst thing that could be said about a rock musician in the era when authenticity and opposition to the establishment were paraded like medals.

It's no wonder that, shortly after, when he arrived in London to give his first concert outside the United States and saw posters all over the place with the phrase "Are you ready for Bruce Springsteen?" the musician got really angry at the excessive publicity and tore down all the posters in the venue where he was scheduled to perform. The concert went well, but he was so affected that for almost three decades he refused to watch the video recording. When he finally did, he realized that, lo and behold, it was a great concert, and it became the fourth live album of his career: Hammersmith Odeon, London '75.

Fifty years after its publication, Born to run It retains an overwhelming energy, an irresistible vitality that may not have been "the future of rock'n'roll" that Landau predicted, but it was one of the milestones of the genre. And the title track maintains its place of honor in concerts: according to Setlist.fm, it is the song he has played live the most times (1,875), followed by another track from the album, Thunder Road (1.584). The musician assures that, for the band, playing Born to run is invested with a certain "sacramental character." And as everyone who has been in it knows a Bruce Springsteen concert, for his fans too.