Mega-salaries for electricity company bosses as electricity prices rocket

Iberdrola CEO Sánchez Galán earns €13m, 171 times the average salary of the company's employees

Electricity prices skyrocketed last year as anyone who pays their monthly electricity bill well knows. This resulted in a sharp increase in the profits of these companies, which tripled, as ARA explained this week. What is not so well known is that during that year six directors, the main executives of large Spanish energy companies, were paid over €27m. In other words, the leaders of these companies were paid 5.2% more while, on average, their workers' salaries increased less than a third of that percentage, 1.5%.

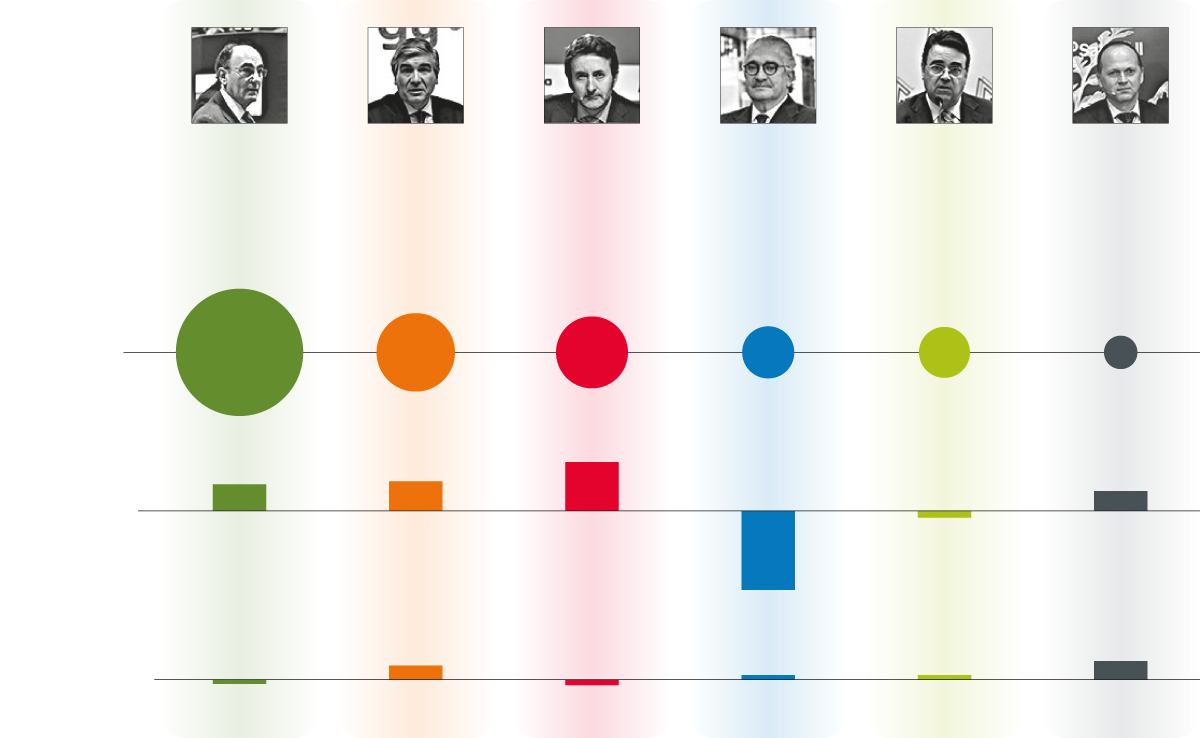

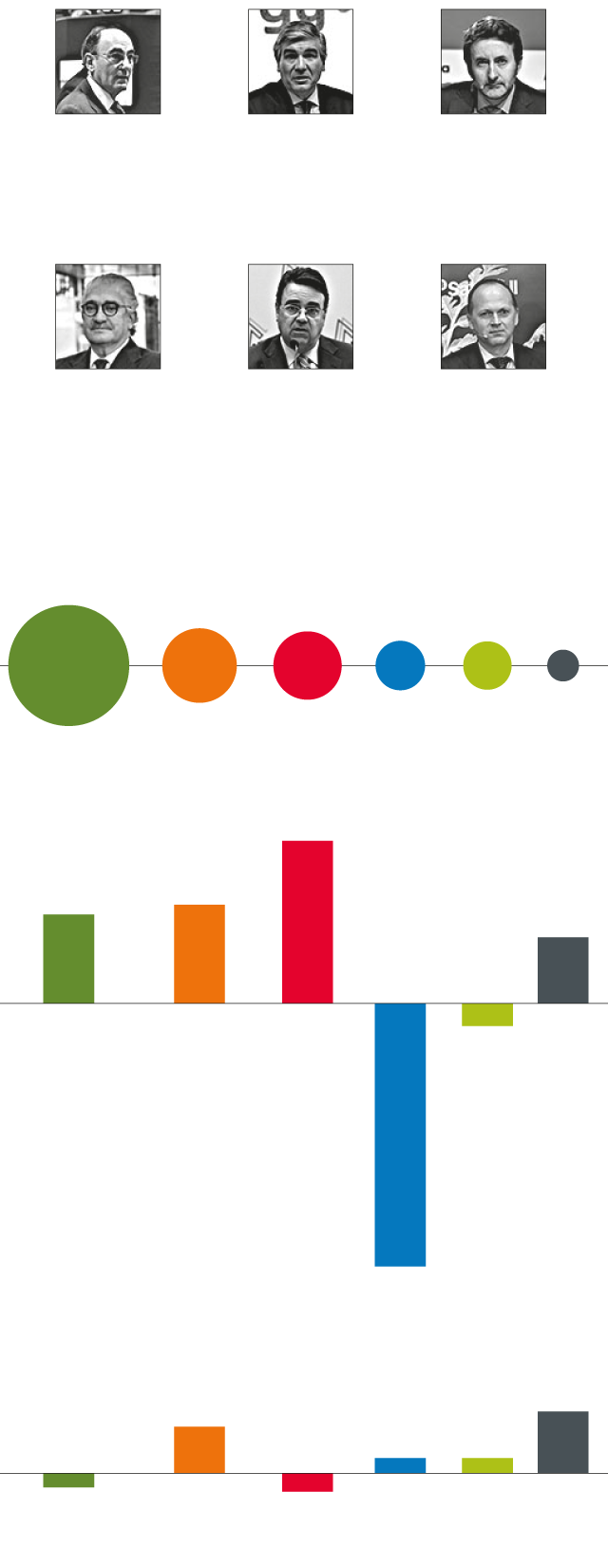

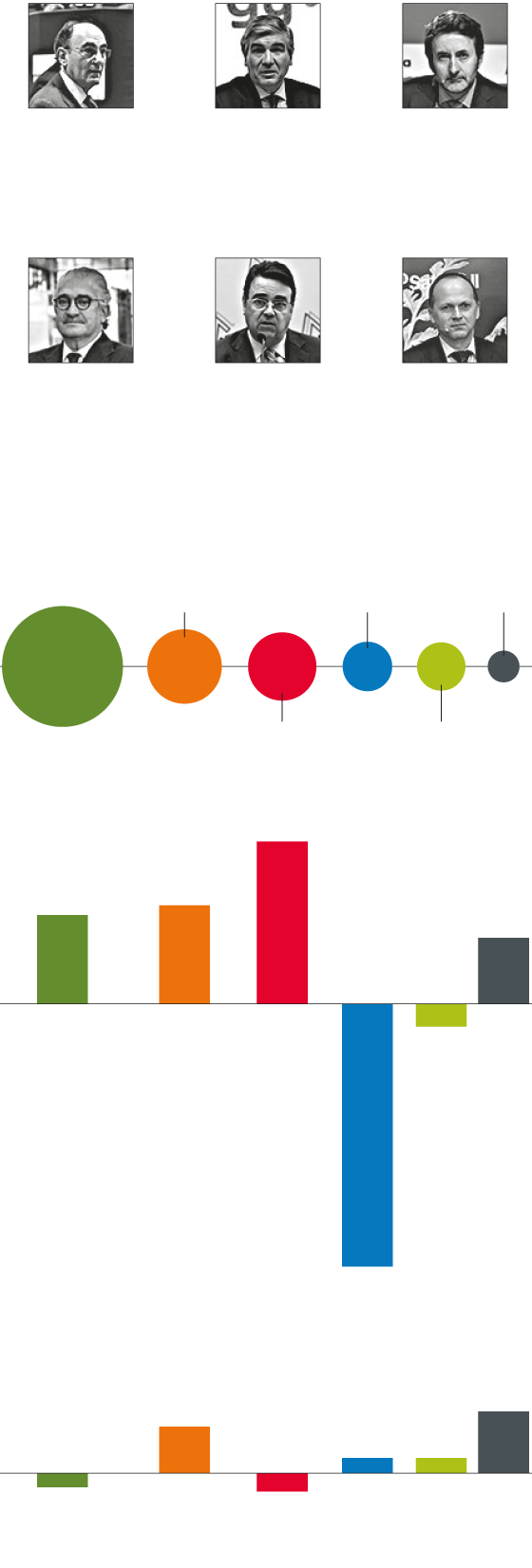

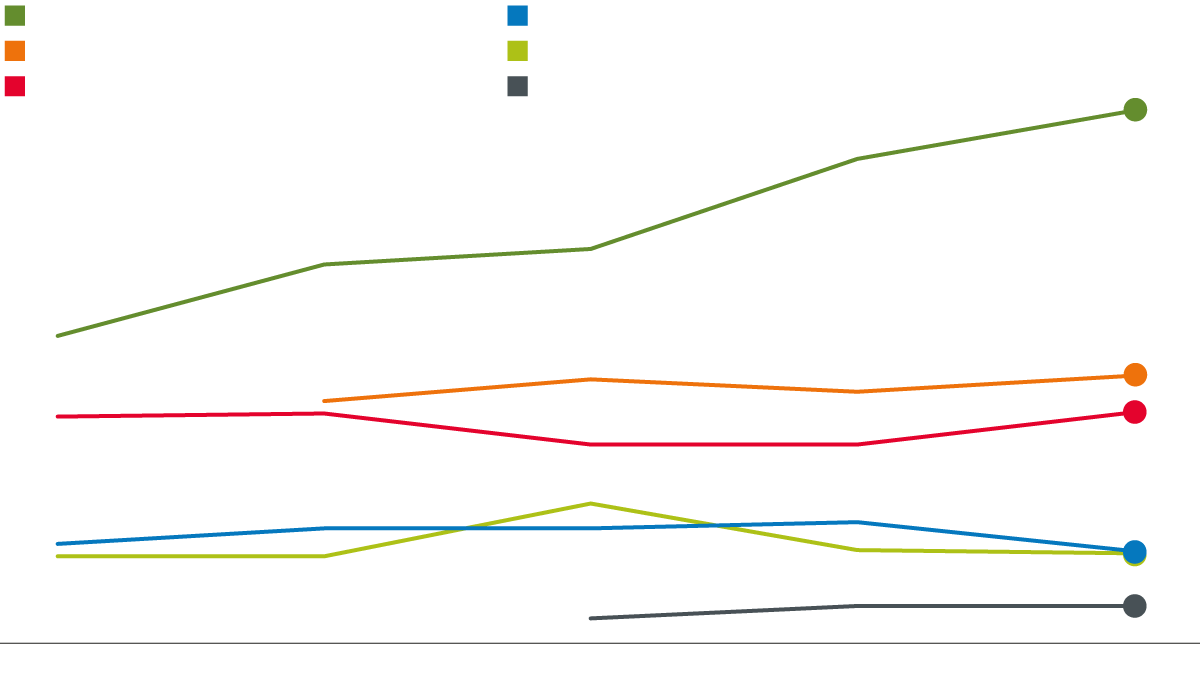

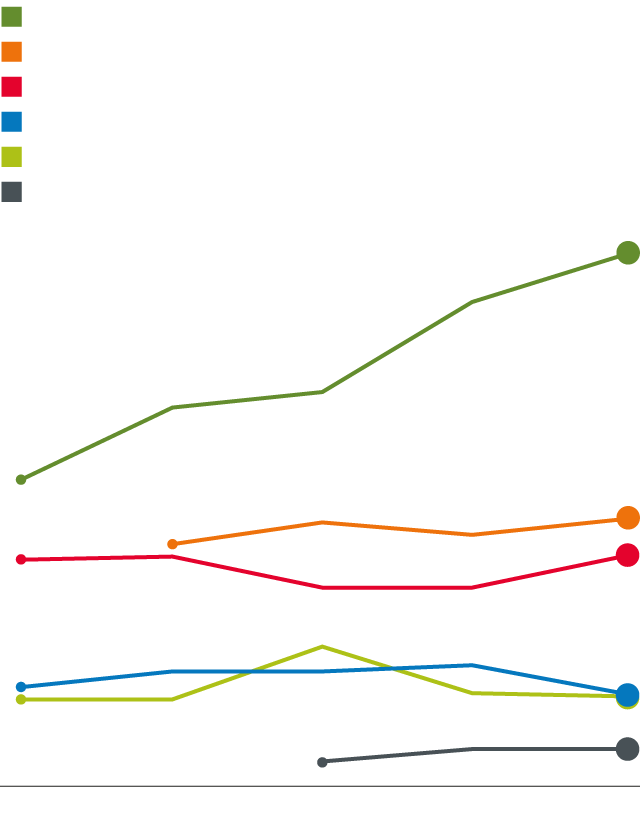

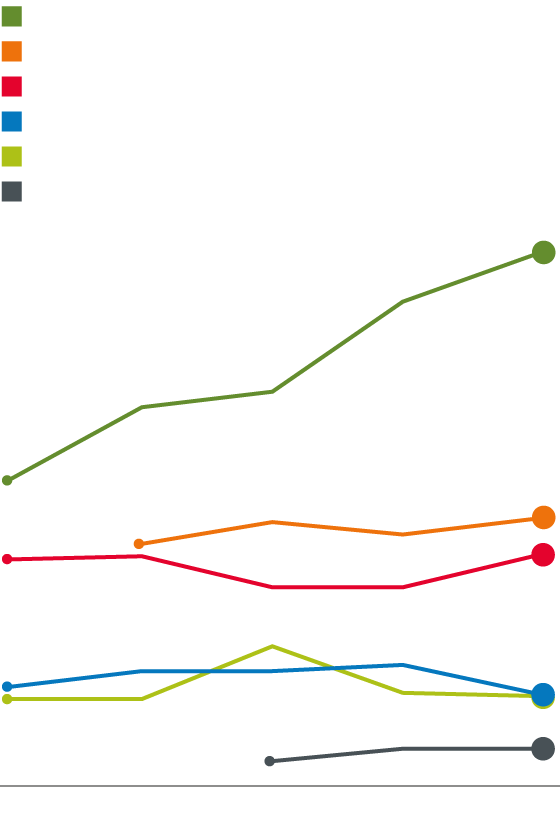

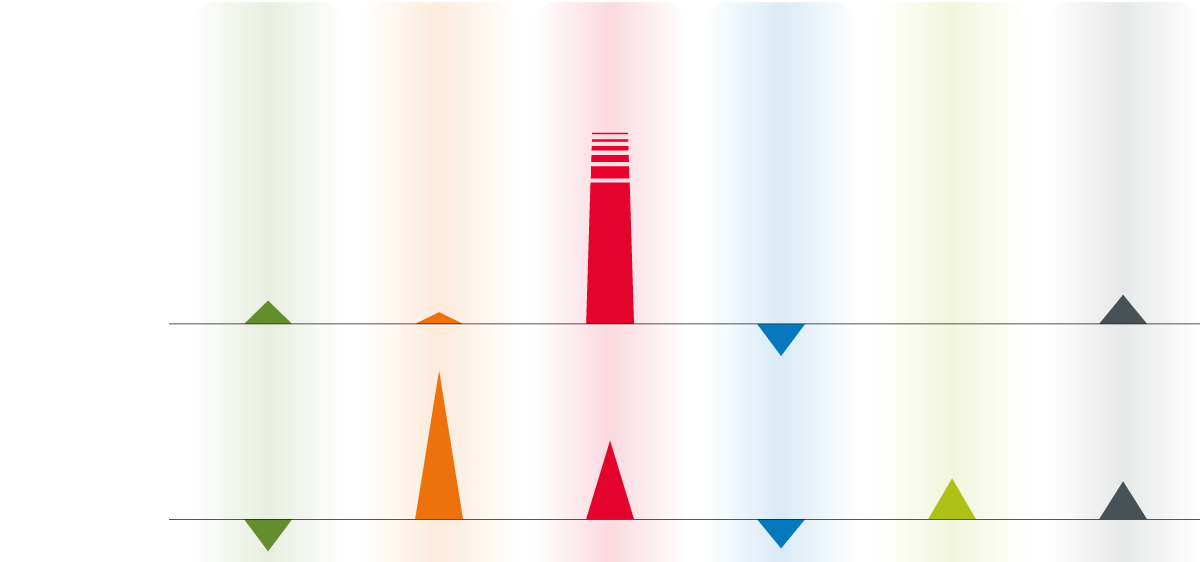

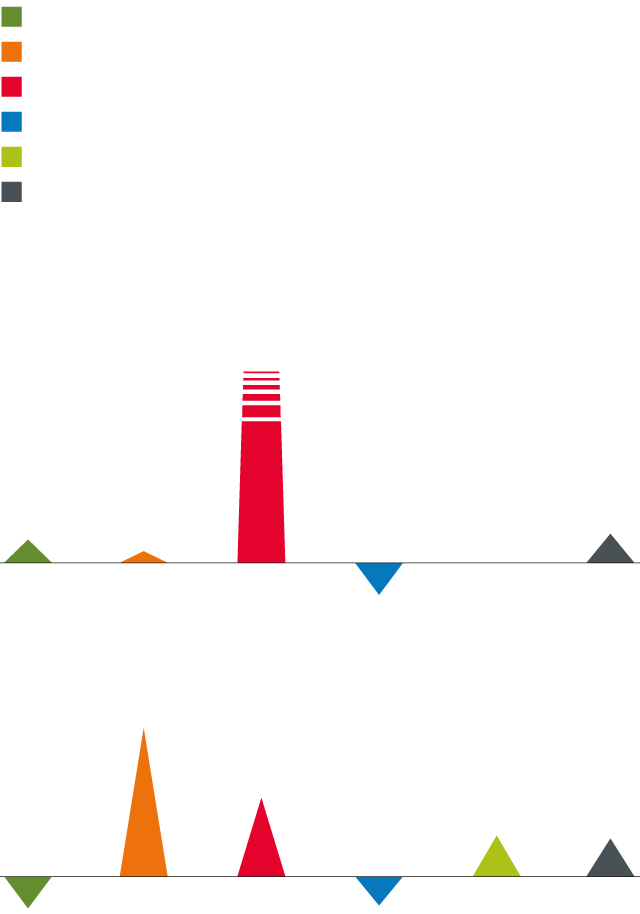

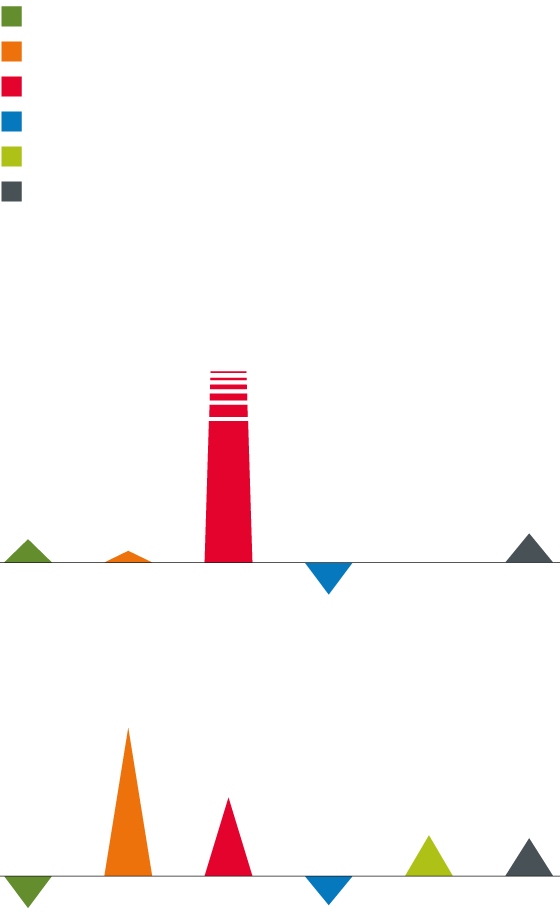

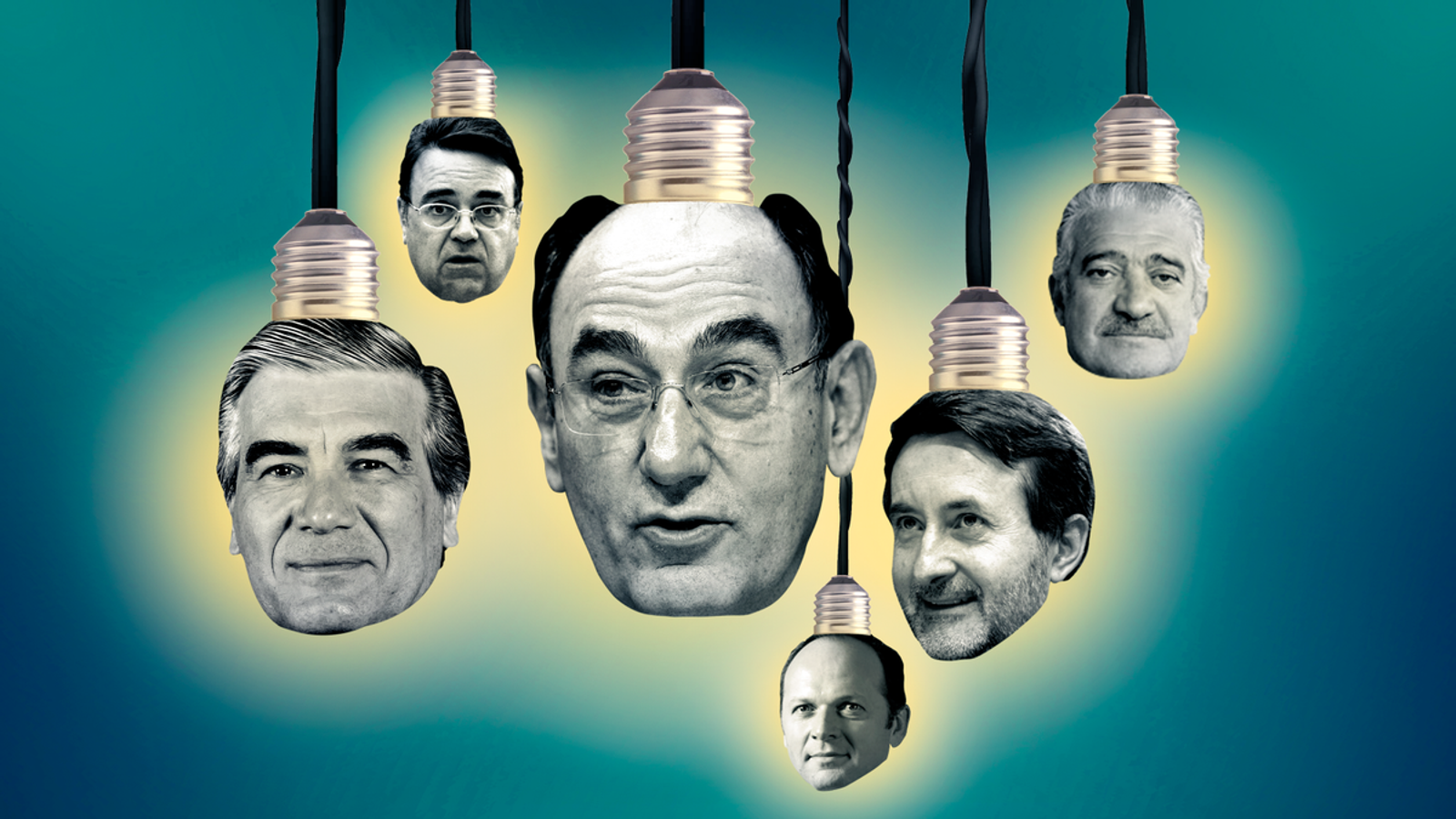

The big winner was José Ignacio Sánchez Galán, chairman and CEO of Iberdrola, who alone earnt almost as much as the other five top executives combined. The controversial Galán was paid €13.2m, an 8% increase, despite the fact that since last June he has been indicted for different crimes linked to the hiring of former police superintendent José Manuel Villarejo for attacking rivals such as Florentino Pérez or Manuel Pizarro, among others. In addition, the average salary of Iberdrola's workers fell by 1.3% last year.

According to the company, a large part of the increase in Galán's salary was explained by a multi-year bonus that was linked to the increase in shares on the stock exchange. But the truth is that Iberdrola's shares fell by 11% during 2021.

The second highest-paid executive was Francisco Reynés, chairman and CEO of Naturgy, who received €5m, a 9% increase. In third place was Josu Jon Imaz, CEO of Repsol, with a salary of €4.2m (up 15%), followed by José Bogas, CEO of Endesa (€2.2m, -24%); Antoni Llardén, president of Enagás (€2.1m, -2%), and Roberto García Merino, CEO of Red Eléctrica (€0.9m, +6%).

One of the most striking aspects when compiling the data that companies themselves are obliged to report to stock exchange regulator CNMV is the comparison between the salaries these executives are paid and the average salary earnt by employees in their companies. Galán, once again, breaks all records, with a salary that is 171 times the average salary of Iberdrola's workers: while the chairman received over €13m, staff received €77,000 on average. The most surprising thing about Galán is that this relation has only grown bigger: in 2017 he was paid 99 times the average salary of his workers and this magnitude has been growing year after year without exception. In contrast, other executives have kept this ratio fairly stable. Reynés is paid 86 times more than his workers (in his first year in office the figure was 78 times) and Imaz multiplies by 74 times the average salary (almost identical to five years ago), for example. The manager with the lowest salary compared to his staff is the head of Red Eléctrica, whose salary is 12 times higher.

This data reopens the eternal debate on how much managers should be paid. What is a fair remuneration for someone who has the responsibility of running an IBEX 35 company?

Although there are proposals such as Christian Felber's – a proponent of the economics of the common good – who suggests that the salary should not exceed 20 times the minimum wage of the organisation, the truth is that there is no mathematical formula. It depends on the industry, the company or even the country where the company operates.

"Coffee for everyone doesn't work," explains Ernesto Poveda, president of Icsa, a human resources company that, among other activities, sets compensation policies. Even so, "making 171 times the average salary of your workers is neither reasonable nor justifiable, and can only be maintained if the company operates in an oligopolistic sector," he adds. Poveda gives an example: with these figures "it is very difficult when negotiating with unions to deny them the right to raise their salaries by 5%".

The role of consultancy firms

Ruth Aguilera, professor of general management and strategy at Esade, warns of the role played by other types of consulting firms specialising in the compensation of these large companies, such as Aon Hewitt, Mercer or Meridian. "The compensation of these executives is decided by the compensation committee [which all listed companies have], but what these committees do is hire a consulting firm that analyses the complexity of the industry, the risks and challenges faced by directors," says Aguilera. However, according to the professor, these consulting firms' fees are set as a percentage of the executive's salary, which creates a perverse incentive. "The CEO is happier if they give them a good salary and so they hire them again, it's a bit inbred," she adds.

Aguilera believes that the energy sector has many difficulties ahead, such as the green transition, and that this could justify a higher salary. At the same time, however, she argues that this not only affects the top manager, but also the rest of the staff, who have to specialise more and therefore also have to be paid more. "The multiplier between the salary of management and the workforce should be stable or decreasing, but not increasing," she concludes.

A final factor to take into account is the increasingly common presence of the shareholders themselves in this type of company. There are large investment companies that are shareholders of the major Spanish electricity companies: BlackRock, for example, is one of the main shareholders of Iberdrola, Repsol and Enagás. And Norges Bank (which manages Norway's sovereign wealth fund, the largest in the world) is a major investor in Iberdrola and Repsol.

The danger of having the same shareholders

This coincidence also generates perverse incentives, according to an article written in 2016 by two Iese professors, Miguel Antón and Mireia Giné, the latter a director at Banco Sabadell. In their opinion, the inflation of super-salaries is related to the growing presence of these "common investors," as they baptize them.Why? Because, if they set high salaries for managers, and especially if these salaries are not linked to the company's performance, they succeed in lowering demands on these managers to compete with their rivals. As a result, according to these professors, investors ensure that none of their investees cannibalises the other companies in which they hold shares.

The article cites data from the United States in which three major investors such as BlackRock, Vanguard and Fidelity vote in favour of compensation 96% of the time, even if it is not linked to the company's results. The forecast of these experts is that, as the presence of "common investors" becomes more and more common, the problem will only increase.

Perhaps we will see this in 2022: what we definitely will see is record high electricity and gasoline prices. What will happen to directors' salaries? We will find out this time next year.