Why does Bukele shave children's heads?

The Nayib Bukele government has taken a new step in its strategy of social control and discipline. Army captain and current Minister of Education Karla Trigueros—a dual position that would be an oxymoron in any state governed by the rule of law—has announced new regulations on school attire. The stated objective: to reinforce student discipline. The measures require students to wear a clean and tidy uniform and, in the case of boys, to adopt an "appropriate hairstyle": a short, uniform haircut that excludes styles popular among young people, such as the Mohawk (crest) or the well-known Edgar court (cup). Those who break these rules face sanctions ranging from lower grades to community service. Images of lines of children waiting to be shaved, more fitting for a military barracks than a school, have gone viral on social media. The question is inevitable: why does Bukele consider it necessary to shave the children of El Salvador? And what symbolic meaning lies behind an element as seemingly trivial as a hairstyle?

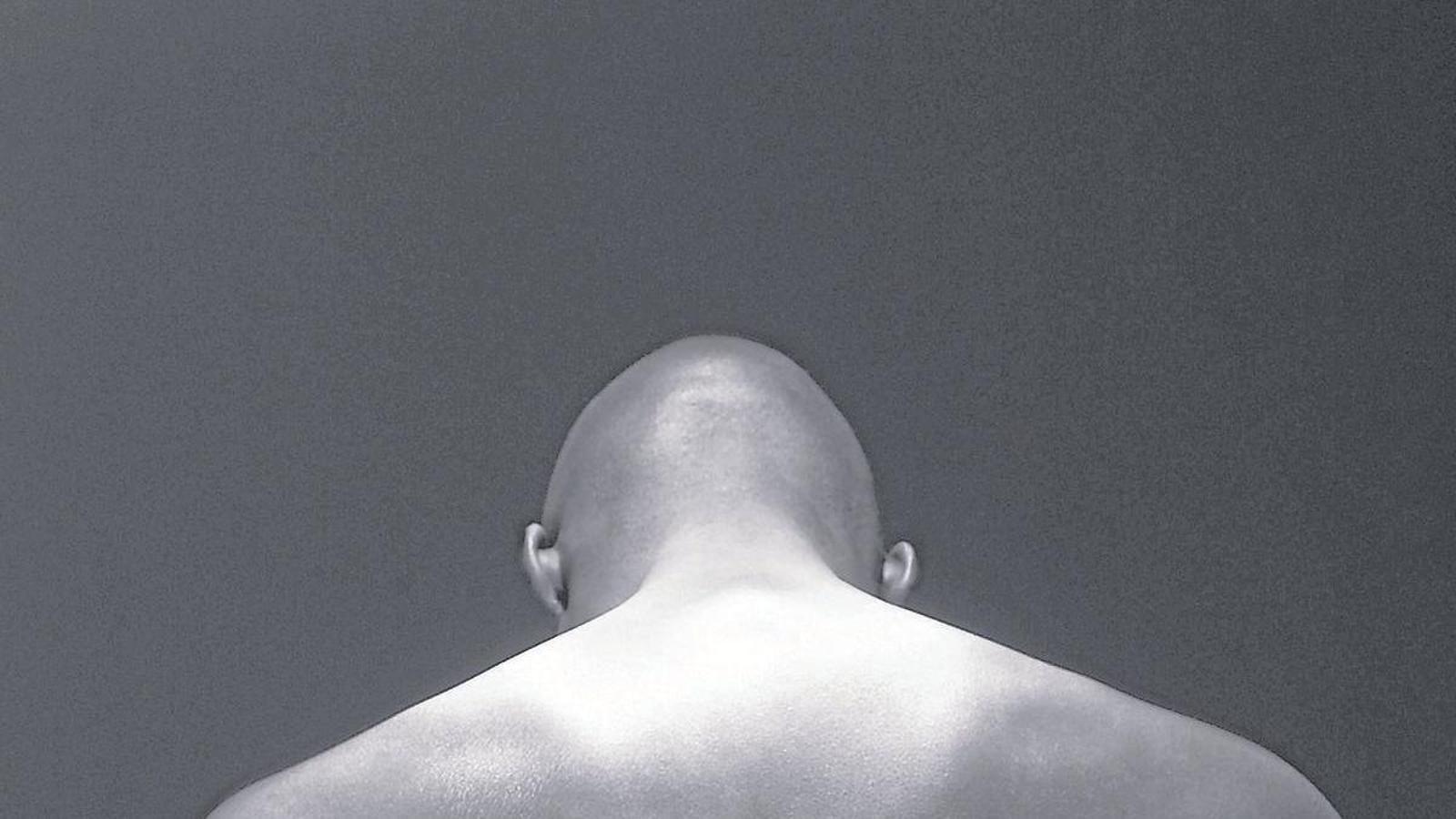

It's hard not to recall the opening sequence of Full Metal Jacket (1987), in which Stanley Kubrick depicts a kind of funeral liturgy: young people sitting in front of a machine that literally takes away part of themselves. What appears to be a simple aesthetic decision actually hides a profound ideological burden. It is justified, on the one hand, by hygienic needs, as it reduces the risk of infection and facilitates maintenance, and, on the other, by safety reasons in combat: long hair can become a vulnerability by offering the enemy a grip. But the true core of this gesture is something else: forced uniformity. All the same, all anonymous. Shaving not only erases individual traits, but also dismantles identities and erodes psychological resistance, which opens the door to dehumanization. It is the plastic staging of the underlying message: the individual no longer belongs to themselves, but is completely subject to the institution.

Shaving is a paradigmatic example of what sociologist Erving Goffman defined as practices of "mortification of the self," common in what he calls "total institutions." It is a calculated process to break down an individual's defenses, erase their identity markers, and reconstruct them in the image and convenience of the institution. It is not exclusive to the military: throughout history, prisons, monasteries, and psychiatric hospitals have shared this ritual of submission, always with the same objective: to placate the will and stifle critical thinking. It has also been seen in civilian contexts, such as when women were publicly shaved after World War II in France, where hair was an instrument of punishment, humiliation, and social control, demonstrating that hair politics has always been a powerful mechanism of domination. This is not a minor detail, but a key mechanism for sustaining authoritarian regimes—like Bukele's—that need to suppress dissent to impose their policies. In this context, fashion and hairstyles, often dismissed as trivial matters, are revealed as central spaces of resistance and individual affirmation. It is no coincidence that the legendary anti-war film Hair (1979) turned long male hair into a symbol of protest and rebellion: what seems superficial can become a flag capable of turning an entire system on its head.

According to the myth of Samson, his hair is a symbol of identity and superhuman strength, and when the Philistines cut it, he loses all autonomy and power to the enemy. Similarly, Bukele shaves children's heads as another strategy to turn Salvadorans into docile, directed, and manipulable bodies. But, as Samson reminds us, the shaved women of France and the rebels of Hair, hair – and with it resistance, ideas and the capacity for rebellion – always grows back, and not even the most disciplinary machine can prevent it from sprouting again.