Wages have not yet recovered from inflation in most developed economies.

Household purchasing power remains below 2020 levels in 21 OECD countries.

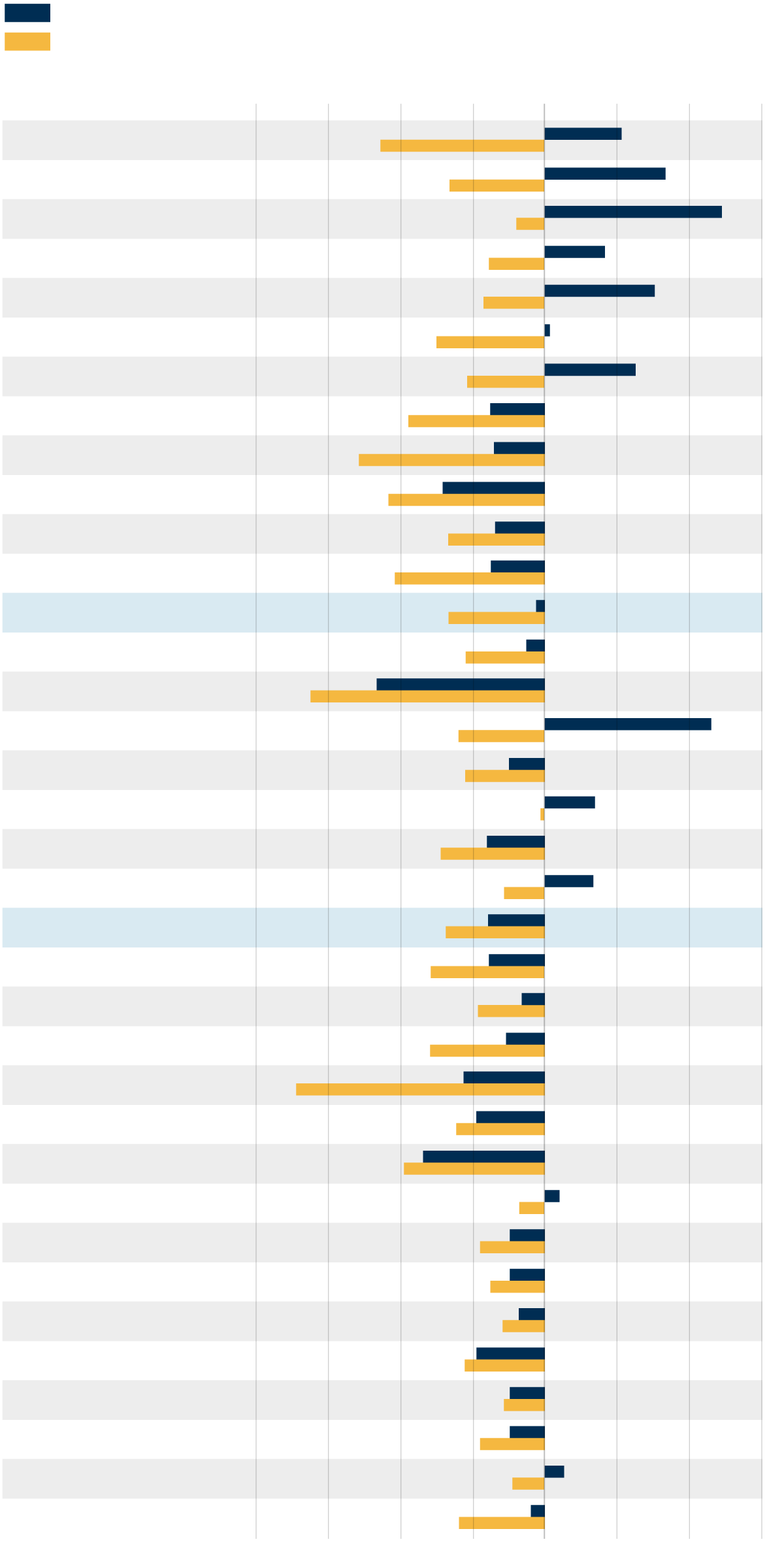

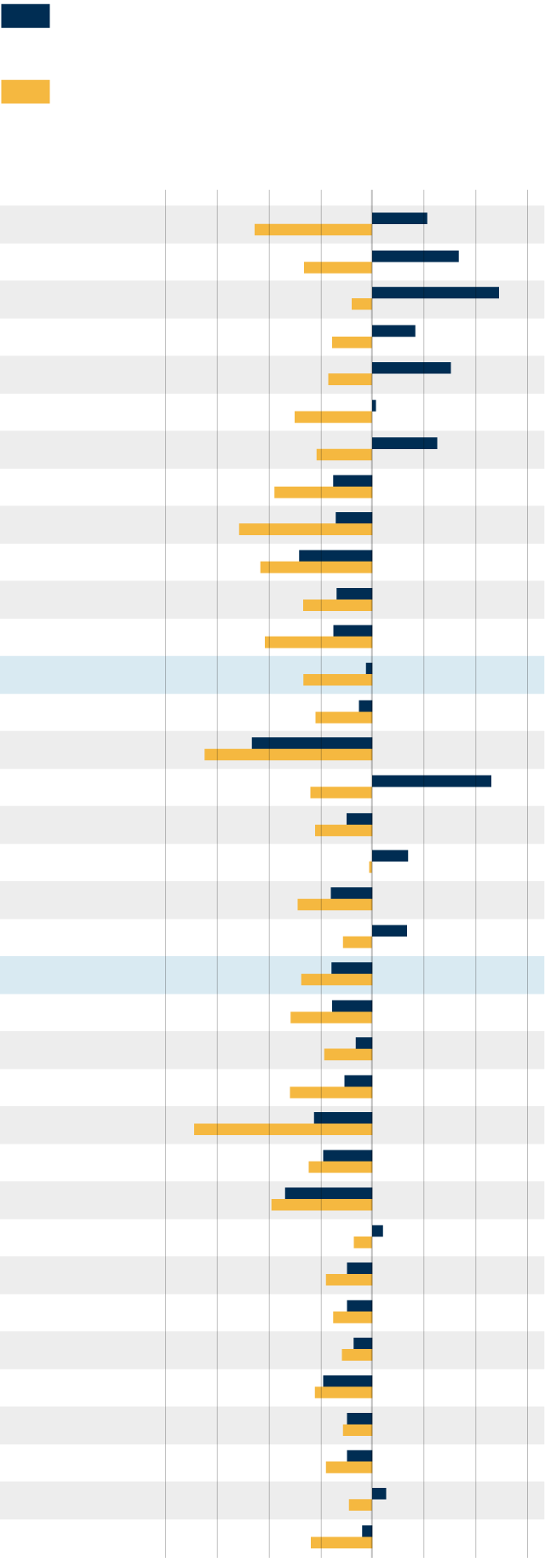

BarcelonaInflation in the years immediately following the pandemic eroded household purchasing power, and in most advanced economies, wages have yet to recover. According to a report by the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD, the umbrella organization of the world's major developed economies), by the third quarter of last year, wages had recovered to the purchasing power they had in 2020 in only 12 of the 33 most advanced countries.

With the reactivation of the global economy with the end of the pandemic and, subsequently, with the energy crisis resulting from the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, most developed economies suffered sharp increases in the prices of consumer goods and services. In Spain, the peak occurred in the summer of last year, when the annual inflation rate exceeded 10%, but in European countries with a greater dependence on Russian gas, the figures reached over 20%.

In this sense, the cost of living for families skyrocketed, while wages remained much more stable. In such a case, the result is a devaluation of wages, which translates into lower purchasing power for the population. This fact has meant that most OECD countries have not yet recovered to the levels of the first quarter of 2021, when the inflationary episode had not yet begun.

In fact, the lack of recovery in the purchasing power of wages is particularly pronounced in the European Union. Of the twelve OECD countries where real wages are already above 2021 levels, seven are EU member states (five of them in the eurozone). The remaining twenty EU countries still have real wages below those of four years ago on average.

The OECD data also study average wages and average inflation, but the effects vary greatly depending on the type of family. Low-income families "were much more affected" by inflation than those with higher incomes or greater assets, since the products in the shopping basket that became most expensive were those most consumed by the poorest households, where, moreover, they must spend a higher percentage of their wages on consumption, says Raúl Ramos, a cathedral professor. "Consumption patterns are very heterogeneous," he comments.

The main "impact" of this price increase, which now seems to be coming to an end, is "an increase in inequality," adds Ramos. This is due to the effect of inflation on consumer goods, but also because "lower wages have grown less" in the vast majority of European countries. "Now we see that there are people who have one or two jobs and can't make ends meet," the UB professor emphasizes.

The slowness of wages to adjust to rising prices is a phenomenon that has been dragging on for decades in Europe and around the world. Its roots lie in the loss of power of unions in processes such as collective bargaining, a result of labor reforms approved across the continent during the crisis and which sought precisely to contain wages. In fact, Spain was one of the countries where a more controversial reform was approved, during Mariano Rajoy's government, which was later amended.

The result of these reforms was that wages rose more slowly, but at the same time there was "less volatility in employment." In other words, wage restraint is the counterpart to preventing unemployment from skyrocketing in times of crisis: Workers earn less, but fewer jobs are also lost. "We must decide, and the debate is there," Ramos notes.

Compensation with the minimum wage

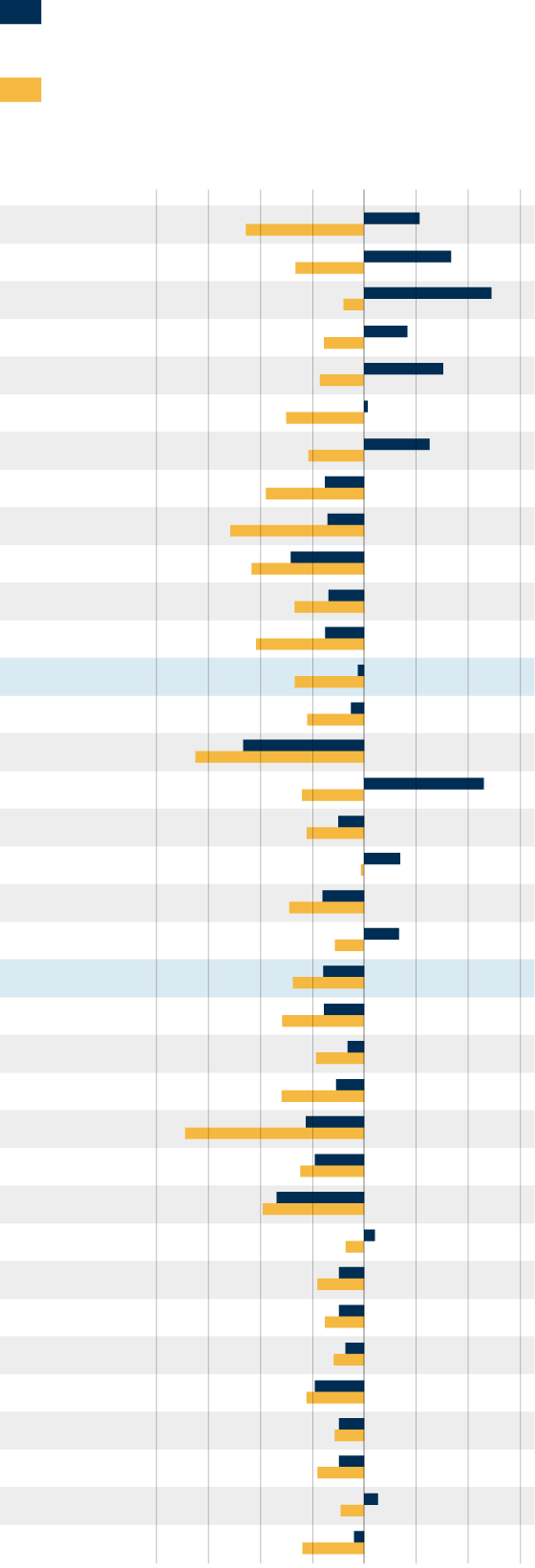

The loss of purchasing power has a direct impact on the well-being and daily life of the majority of the population. In response, governments have approved minimum wage increases in most OECD countries. "It's a response: governments have made a decisive commitment to raising the legal minimum wage," says Ramos, referring to most European countries.

In this regard, the OECD figures are clear: "The actual legal minimum wage was higher in January 2025 than in January 2021 in virtually all 30 OECD countries that have one," the organization's report notes. On average, this increase was 8.8%, while the median wage (that is, the one with 50% of salaries below and 50% below) grew less, by 5.5%, according to the study.

This policy's primary objective is to alleviate the effects of inflation on lower-income families and, therefore, prevent inequality from growing even further. However, it has an effect on other wages, since the minimum wage usually acts as the minimum against which all workers compare their salaries. Thus, when the minimum wage rises, so do all other wages, because many workers demand increases despite initially earning more than the minimum wage.

This increase in the minimum wage has a direct impact on household consumption, one of the pillars of economic activity. The higher the income, the higher consumption generally rises, but academics agree that wage increases for lower-paid jobs have a greater positive impact because a large portion of the increases are dedicated to consumption, whereas if the person receiving a pay raise already has a higher salary, they will likely put the additional money toward savings or investments.

Ramos believes the minimum wage increases will continue, at least for the foreseeable future. "The fight against inequality will remain on the political agenda," he predicts. However, he adds that it will not be the only factor to consider. For example, the monetary policy of the European Central Bank—and, indeed, of most central banks—has been restrictive until recently, with interest rate increases precisely to curb inflation, but with the negative effect of making credit more expensive for indebted families and making it difficult for companies looking to invest.

However, with inflation at 2%—the level the ECB defines as optimal for the long term—in the eurozone, the ECB has been cutting interest rates again for months. This could boost economic activity and business investment, increasing demand for labor by companies and, therefore, putting pressure on them.