Why is Neil Gaiman's latest comic so uncomfortable to read?

The story of 'Miracleman: The Silver Age' makes it very difficult to separate the work from the author, who has been accused of abuse by several women.

BarcelonaThere are comic series with bad luck, others that seem cursed and then we have MiraclemanThe publishing trajectory of this character is a fascinating nightmare that, in some ways, serves as a mirror to the structural problems and dysfunctions of the American and British comic book industries. Suffice it to say that the book documenting the character's tortuous publishing adventure is titled Chalice poison. The extremely long and incredibly complex story of Marvelman (and Miracleman) [Poison Cacio. The extremely long and incredibly complex history of Marvelman (and Miracleman)]. It was published in 2018, when the legal battles and authorship disputes that paralyzed the publication of the series for more than three decades seemed finally resolved; however, what the author of the book, the Irishman Pádraig Ó Méalóid, didn't know was that the most sordid and unexpected chapter in the story would end up being written in 2025, and would star Neil Gaiman.

But let's get down to brass tacks. In 1952, after more than a decade of litigation between the publishers National and Fawcett, an American court ruled that the character of Captain Marvel—later renamed Shazam to avoid conflicts with the publisher Marvel—was a rip-off of Superman, and the series closed. As a result, the publisher that published Captain Marvel comics in the United Kingdom commissioned English cartoonist Mick Anglo to try his hand at a similar character. Without giving it too much thought, Anglo created Marvelman and Young Marvelman, British-style variations on Captain Marvel and his juvenile partner, Captain Marvel Jr. The weekly black and white adventures of the new characters became a minor sales phenomenon until 1960, when the British government lifted the ban on importing American comics and Marvelman's popularity declined, leading to the series being cancelled in 1963. ~BK_SLT_NA One of the readers of the series was Alan Moore (Northampton, 1953), a future star comic book writer, who enthusiastically accepted the proposal in 1982 to revive Marvelman in the English magazine. Warrior. Moore didn't just update the character, but introduced a revolutionary concept: placing the superhero figure in the real world and exploring the extreme tension and violence that this would generate, but without resorting to conventions of the superhero genre. The series, renamed Miracleman For the North American market –again to avoid confusion and conflicts with Marvel–, it was the first stone of the revisionist current of the superhero genre that Moore himself would culminate with Watchmen and which were later embraced with more or less success by countless comics, but also by films (Kick-ass) and television series (The boys).

Although he was on the verge of abandoning the series several times due to conflicts with the editor of Warrior and with the American publishing house Eclipse, Moore completed his time in Miracleman masterfully and brought the series to its unique conclusion logic: the all-powerful superhero established himself as the benevolent dictator of the Earth, ending all wars, hunger, and injustice. This disturbing utopia is what a young Neil Gaiman (Portchester, 1960) found in 1988 when Moore offered him to continue the series. A major challenge that the screenwriter of Sandman resolved magnificently with a handful of stories that explored the dark side and contradictions of a perfect world ruled by a pantheon of near-divine beings.

Miracleman: The Golden Age [Miracleman: The Golden Age] was the title of this first batch of episodes drawn by Mark Buckingham, which Gaiman wanted to continue with two more story arcs, Miracleman: The Silver Age [Miracleman: The Silver Age] and Miracleman: The Dark Ages [Miracleman: The Dark Ages], through which to show the fall of this utopian society. However, he couldn't do so due to the financial problems of the Eclipse publishing house, which went bankrupt in the early 90s. The legal conflict that began at this point is twisted and tortuous, with many versions and twists and turns, but the summary is that Gaiman litigated for two decades with the cartoonist Todd Mc9 over Eclipse's trademarks and intellectual properties, and with whom Gaiman already had an ongoing lawsuit over three characters that the screenwriter had created in the series. Spawn in 1993.

An unexpected miracle

The resolution of the conflict came in the most unexpected way when it was revealed in 2013 that, after all, the intellectual property of Miracleman had never belonged to Gaiman or Moore or, of course, McFarlane, nor to Eclipse or the publisher of Warrior, but by the artist Mick Anglo, who was still alive. Marvel acquired the rights and announced the first complete reissue of the series in more than two decades – but without including the name of Alan Moore anywhere, who wants nothing to do with Miracleman– and the return of Gaiman and Buckingham to close the story they had left unfinished in 1993. Bombshell news, especially given the cult status they had achieved so much Miracleman like Gaiman, considered a genius of modern fantasy and pursued by all platforms, eager to adapt his stories to the screen.

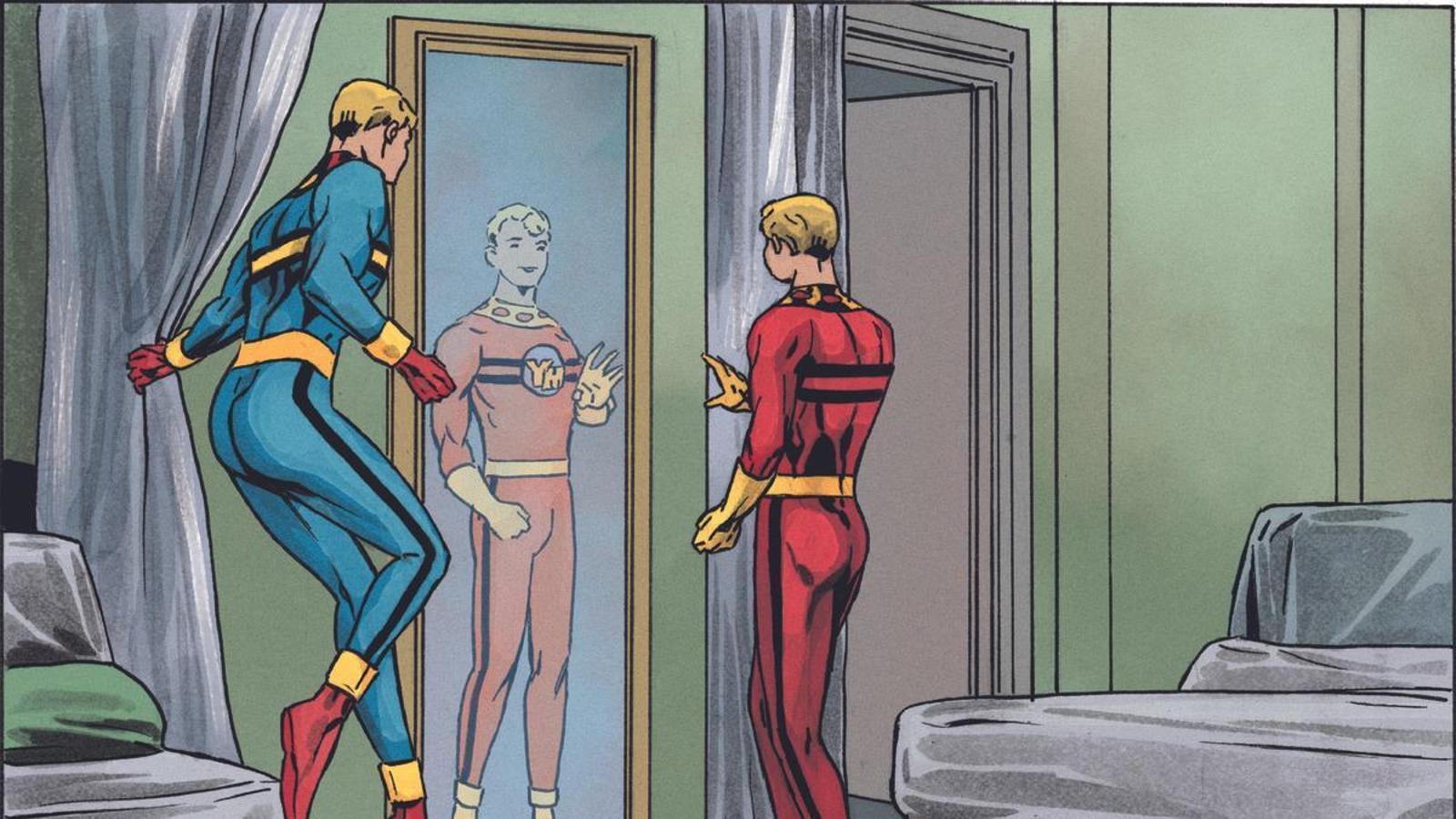

However, the arrival in bookstores of Miracleman: The Silver Age, published in Spain by Panini in Spanish last May, wasn't the event that was expected. Nor was it in the United States, where the six episodes were first published in stapled format and finally compiled into a book. Neither did it achieve stratospheric sales nor enthusiastic reviews, despite general praise for Buckingham's elegant and exquisite artwork. It must be said that it's not a bad superhero comic nor a disappointing continuation of the Miracleman saga. Quite the opposite: in the utopia created by Moore, Gaiman reintroduces Young Miracleman, a character from Mick Anglo's original run, who is added to the superheroic Miracleman pantheon and transformed into a deity worshipped by the masses while he tries to adapt to this strange world and accept that the innocents didn't exist.

But the real shock comes when his old friend Miracleman decides to apply a supposed psychological shock therapy and, without asking permission, gives Young Miracleman an unequivocally sexual kiss, an aggression that provokes in the bewildered young man a defensive explosion of rage and violence. Although unexpected, the twist is consistent with the DNA of the series, which in the Alan Moore era already showed with a realism unprecedented in superhero comics the rape of a character, the teenager Johnny Bates. The scene in question triggered the return of his alter ego evil and powerful, Kid Miracleman, and ended in the absolute destruction of London, a massacre of chilling violence and cruelty.

A The Silver Age, Miracleman's unwanted kiss triggers Young Miracleman's escape, setting off on a quest to find his roots and ultimately unlocking the repressed memories of the abuse he suffered as a child in an orphanage, where he was raped by several men. Gaiman's script tactfully and modestly explores the trauma of sexual abuse and the wounds it leaves behind. When the superpowered girl with him asks if she can kiss him, he replies with touching fragility: "No one's ever asked me before."

Uncomfortable and disturbing

The problem of The Silver Age is that this plot, which is the heart of the story, is terribly uncomfortable and disturbing to read after knowing the sexual abuse allegations against Neil Gaiman in the last yearSeveral women have offered testimony about rough, sadomasochistic sex practices carried out without full consent. These accounts, especially in the case of young Scarlett Pavlovich, who worked as a nanny for Gaimán's son, reach shocking levels of brutality. First, four women accused the writer on the podcast. The Tortoise, and then the New York Magazine spoke with them and four other women, who identified abusive behavior in their relationships with the writer, who has denied the accusations and said he has never had non-consensual sex with anyone.

Gaiman has always presented himself as an activist for the feminist cause, and his work is not lacking in examples. Such as Wanda de Sandman, one of the first trans characters portrayed with respect and dignity in comics of superheroes; or the importance and abundance of realistic and complex female characters in his works, especially during the time when comics mainstream sexualized and stereotyped most women. How, then, to manage the flagrant contradiction—or pure cynicism—between the discourse and the actions of which Gaimán is accused? Is it possible to separate the work from the authorship when the clash between the two is, apparently, so violent?

Following the accusations, all audiovisual projects related to Gaiman's work have been canceled or ended ahead of schedule; this is the case of the series Good omens and Dead Boys Detectives and the failed film adaptation ofThe Cemetery Book. It has also been closed Sandman, which has concentrated all the remaining plots into an intense second season finale that ends, like the comic, with a high-profile death and funeral. It's fitting: the writer's career also seems doomed, even in the comic book world. While the conclusion of the Miracleman Gaiman's was one of Marvel's big prestige projects, the head of the publishing house, Tom Brevoort, declared in February that they had no plans to publish The Dark AgeIt seems unlikely, therefore, that the final act of the story Neil Gaiman began in 1988 will ever see the light of day. The latest stumble in the publishing history of Miracleman, the superhero with the best scriptwriters and the worst luck.