The photographer who defeated a bloodthirsty Belgian king

Amador Guallar brings back from oblivion Alice Seeley Harris, who documented the atrocities committed by Leopold II in the Congo.

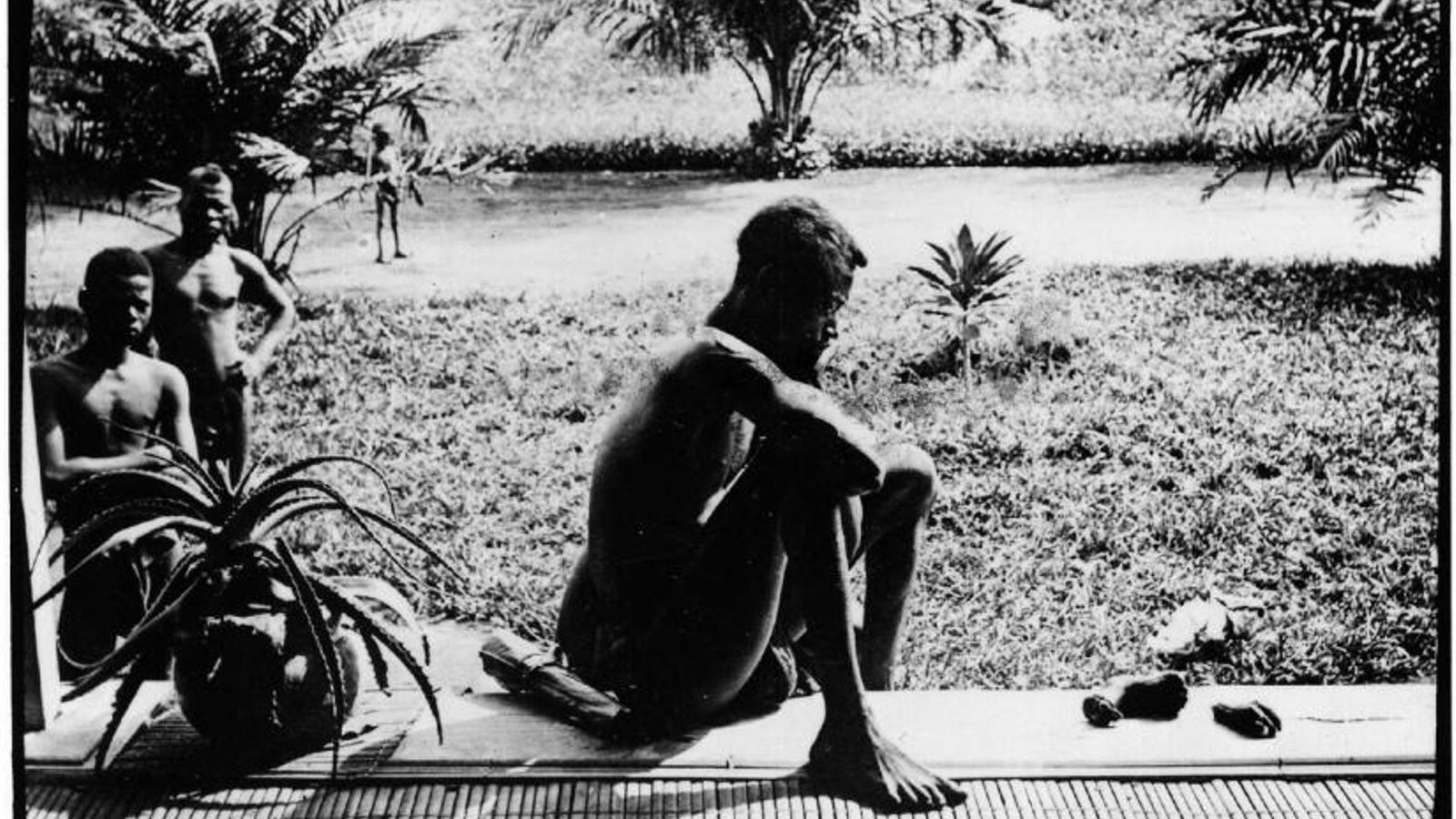

BarcelonaBritish woman Alice Seeley Harris (1870-1970) entered the Congolese forest with her husband in 1898. As a missionary with the Regions Beyond Missionary Union, Alice carried the "word of God," but also a primitive Kodak camera that increasingly suits her. She witnessed and documented the crimes committed by the Force Publique (FP), which, on behalf of the Belgian King Leopold II, committed all kinds of atrocities in Congo.

Seeley Harris's photographs were crucial because Leopold II, One of the bloodiest leaders of modern times, he renounced his fiefdom: a territory in central Africa as large as half of Europe, which he ironically named the Congo Free State in 1885. For two decades, the Belgian king gave free rein to the most depraved greed: he exploited the territory, became immensely rich, and was responsible for the deaths of millions of people—half of the Congolese population at the time; estimates range from the two to ten million victims.

Seeley Harris was brave and a pioneer. "Not only did she help with her photographs to end one of the worst genocides in history, but she was a pioneer of journalism. Long before Robert Capa, Chim (the pseudonym of David Seymour), Henri Cartier-Bresson, or Ansel Adams, there was Alice," explained the journalist, writer, and photographer (1978). Guallar, who has extensive experience as a war correspondent, collects the story of Seeley Harris in Kodak in the Congo: The Forgotten Life of Photojournalism's Pioneer (RBA).

"I discovered it when I was in the Central African Republic reporting on the PK5 militia. A journalist told me about it. I'd never heard of it before, even though I studied journalism, I'm a photographer, and I've read a lot of books about journalism. Her story wasn't just hers, it was hers. She's listed as the author. There are even books she'd written, like Dawn in darkest Africa, which have been attributed to her husband," says Guallar, who becomes indignant when explaining how this photographer was not only "robbed" of her work but also of all her efforts and achievements.

"She was the first to show that a photograph can change everything," emphasizes Guallar. small village of Wala, in the Upper Congo, where she observed the hands and feet torn off her five-year-old daughter.

Alice Seeley Harris was a pioneer in many other ways. "She was one of the first to use the magic lantern, a proto-camera that worked with slides and which she used at the conferences she gave in the United States and Europe to denounce the crimes in the Congo," says Guallar. The photographer joined forces with the British diplomat Edmund Dene Morel and the poet and diplomat Roger Casement, who fought for Irish nationalism and was eventually executed by the British during World War I. The writers Mark Twain and Arthur Conan Doyle, who were admirers, also used Seeley's photographs in their denunciations of Leopold II. The Belgian king burned the archive containing all the documentation on the Congo Free State before his death.

Seeley Harris's victory has a bittersweet note. After two years of litigation, in November 1908 the Belgian king agreed to transfer the African country but in exchange for fifty million francs. He died immensely wealthy and was honored.

Museums also refuse to recognize Alice's authorship.

Even now, the photographer is not widely recognized. When she turned 100, she was interviewed on the BBC. In 2015, an exhibition of her photographs was held. Brutal exposure: the Congo, in 2015 at the International Slavery Museum in Liverpool. Most of his work is stored in boxes at the headquarters of Anti-Slavery International, the successor to the Anti-Slavery and Aborigines Protection Society, in Brixton, England.

"A month ago I was at the Royal Museum for Central Africa in Tervuren (Belgium), and the reference to the genocide is on a half-hidden panel; there are no death tolls or acknowledgment of the genocide. They also have two large statues of Leopold II, which he achieved in the Congo," says Guallar. In one room of the museum, there is one of Edmund Dene Morel's books, and a small television is showing some images. "There are some about Alice, but there's no record of the authorship," explains Guallar.

Even today, many of the photographs taken by the photographer are attributed to her husband, who was secretary of the Anti-Slavery Protection Society and an independent member of the Liberal Party in the British Parliament. John Harris was knighted, and Alice Seeley Harris was made a dame. Seeley Harris was also an active suffragist and, in fact, used the title "dame" in her campaign for votes for women: "Don't call me a dame!" she told British journalists.